Advances in technology mean that aircraft in the North Atlantic High Level Airspace (NAT HLA) are flying laterally, longitudinally, and vertically closer than ever before. But North Atlantic gross navigational errors (GNE’s), which are lateral off-track deviations of 10nm or more, still occur regularly, and jeopardise the safety of you and the traffic around you. So don’t leave it up to Air Traffic Control (ATC) to discover your GNE! In this article, let’s look at some common human slip up’s that lead to GNE’s, and what we can do to prevent them.

[heading]Pre-Flight[/heading]Operating to the highest standards of navigational performance demands the tedious and careful monitoring of aircraft systems. Unfortunately, humans are by nature not the best monitors. During the long quiet of an oceanic crossing, we can fall victim to cognitive traps such as change blindness, expectation bias, and complacency.

But the potential for error on Atlantic crossings begins well before the first coast-out waypoint. In fact, it begins before take off. The following four areas are where strategies in mitigating a GNE begin.

1) Data Entry

Via ACARS:

Many pilots now use ACARS to automatically downlink the entire flight plan and winds aloft directly to the FMS. But an over-reliance on automation can lead to complacency, and so the more reliable the system, the more complacent we become as monitors. In one incident, a Boeing 747 suffered a GNE of 120nm. The flight plan downlink from ACARS unfortunately contained one bad coordinate that went unnoticed. Once lured into complacency by such reliable technologies, there can be a temptation to omit cross-checking.

What can we learn from this? Always verify the full coordinates in an ACARS downlinked flight plan. Similarly, if several different flight plans were run, ensure that you request your downlink using the most current and filed flight plan number.

Manually:

A manual entry means a pilot inserts the flight plan’s waypoints directly into the aircraft’s flight management system (FMS). But no matter how meticulously one may be, manual data entry can still produce errors. Then how do we guard ourselves against these errors?

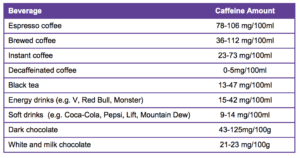

Firstly, avoid using ARINC 424 shorthand for programming oceanic points. This has been a factor in many GNE’s, given how easy it is to misplace the letter as a prefix or suffix. For instance, consider how simply misplacing the “N” could cause a drastic lateral deviation:

- 50N60 = 50N 160W

- 5060N = 50N 060W

If you have the capability on your aircraft, use the full coordinates, including minutes.

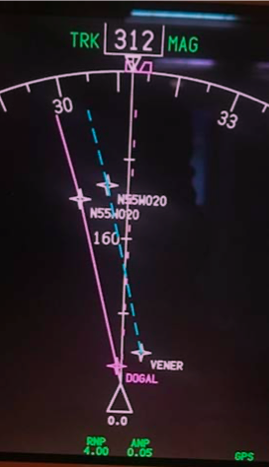

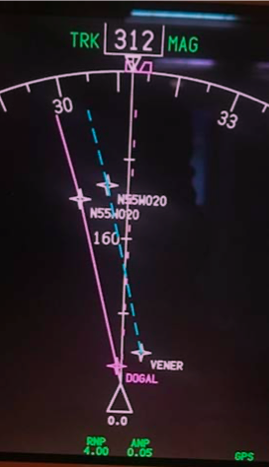

For the last few years, use of half degrees of separation has been on the rise in an attempt to enhance airspace efficiency. But on flight displays units that only show 7 digits, these half degree coordinates are misleadingly displayed as full coordinates. For instance, the half coordinate N55°30’ W020° will display as N55°W020° (see image below, which shows identical waypoint labels for points separated by half a degree!). In this case, it is imperative to view the expanded version of coordinates (degrees and minutes).

Another frequent error leading to GNE’s is transposing numbers during data entry. This commonly occurs when you complete almost the entire crossing along one degree of latitude, then fly the last waypoint at a different latitude. For example, with a cleared route of 57°N 050°W, 57°N 040°W, 57°N 030°W, 56°N 020°W, one can accidentally enter 57°N 020°W. This will put you 60nm off course.

But there is good news! These errors are easy to recognize and avoid by having a specific method of waypoint verification.

2) Waypoint Verification

Whether entered via ACARS or manually, both crew members must come together to perform a thorough cross-check. The following method recommended by ICAO in Doc007 seems to work the best:

- One pilot reads the waypoint/coordinates, bearing and track from the FMS.

- On the master document, the other pilot will circle the waypoint to signify the insertion of the correct FULL coordinates in the navigation computers

- The circled waypoint number is ticked, to signify the relevant track and distance information matches

- (In flight) The circled waypoint number is crossed out, to signify that the aircraft has overflown the waypoint.

[fancy_box box_style=”default” icon_family=”none” color=”Accent-Color” border_radius=”default” image_loading=”default”]

Cognitive Traps:

Expectation Bias is when your perception is influenced by your preconceptions. It is vital that the second crew member crosschecks from the FMS/CDU to the master document – and not vice versa – thereby increasing the chance of spotting an error.

Pop-up trip hustle – It’s one thing reading about waypoint verification, but it’s another thing actually sitting down and taking the time to do it. Do not be tempted to crosscheck your own work because you’re in a time crunch – it requires at least two separate sets of eyes.[/fancy_box]

3) Initialisation of navigation systems

The navigational integrity of your entire flight is predicated on an accurate starting position. Even a small error with on the ground can translate into a gross error later down the line in flight.

The FMS GPS position and your current parking coordinates (found on the 10-9 pages) must match. Avoid using “last position” function in the FMS – if you were towed overnight, the “last position” will be your previous location, not your current one! Sounds obvious, but mistakes happen.

Inertial systems, once aligned, must also complement the GPS coordinates. Initialisation of inertial navigation systems can take between 6-15 minutes, and errs on the longer side at more northerly latitudes – so be patient! Moving the aircraft during alignment will cause an alignment error. Bottom line: avoid repositioning/towing the aircraft during alignment, even it is to a nearby spot on the same ramp area. Position errors like this cannot be corrected once in flight.

4) Your Master Clock – (iPhones not authorised!)

Since our ETAs for oceanic waypoints must be accurate within +/- 2 minutes, it is vitally important that, prior to entry into the NAT HLA, your master clock is accurately synchronised to UTC. ICAO Doc007 has a list of approved sources from which you can set your aircraft master clock (and your iPhone isn’t one of them!). You are approved to use the GPS time which can be found in the FMS.[fancy_box box_style=”default” icon_family=”none” color=”Accent-Color” border_radius=”default” image_loading=”default”]

Cognitive Trap:

Close to the E/W Greenwich line or close to the equator, you’ll just be on the fringes of the opposing segment. So, take a close look at the E/W or N/S letter coordinates, especially if you are usually accustomed to flying from one particular geographic area.[/fancy_box][heading]Clearances & Communication[/heading]With a move away from spoken communications and towards datalink procedures, requesting, copying and verifying a clearance becomes a much simpler task! But it is still important to know your own limitations in the rare instance that you need to copy a clearance via voice.

Casual radiotelephony should be avoided

Casual radiotelephony can be the source of misunderstanding coordinates or clearances, and so all waypoint coordinates must be read back in detail, adhering strictly to standard ICAO phraseology. An example of standard ICAO phraseology requires enunciation of every individual digit. 52 North, 030 West would be read back as “Fife two north, zero tree zero west” as opposed to “fifty-two north thirty west”. Have no doubt about it, Shanwick can be the most strict in this regard.

Distractions and workload

If your departure airport is close to the oceanic boundary, e.g. Shannon or Miami, the benefit is that you will copy your oceanic clearance on the ground. Unencumbered by distractions typically associated with being in flight, you can focus almost fully on the task at hand. However, most flights pick up an airborne clearance, and it is important to prioritise this for a period of low workload.

Take the example of a Bombardier Global Express crew that narrowly avoided a GNE after copying a clearance. While they were in the midst of crosschecking the clearance with the FMS and climbing to their initial altitude, the flight attendant approached them with an issue. Instead of waiting, one of the pilots attended to the problem. A new waypoint wasn’t entered, and it was later caught by ATC in a position report. Try to avoid non-vital tasks until ALL the steps regarding copying, verifying and inputting a clearance are complete.

Following these simple standard operating procedures (SOPs) step-by-step will guard against clearance errors. If the steps are interrupted for any reason, start again from the beginning.

- Two pilots monitor and record the clearance. The Pilot Monitoring (PM) will contact clearance delivery, while Pilot Flying (PF) monitors both the primary ATC frequency and the clearance delivery frequency.

- The PM then records the clearance on the master document. The PF also copies down the clearance separately.

- Clearance is read back to ATC. Any disparities between both pilots’ interpretations of the clearance must be clarified with ATC.

- A deliberate cross check of the clearance to the filed flight plan and the FMS is made.

Re-Clearance

According to ICAO Doc007, “In the event that a re-clearance is received when only one flight crew member is on the flight deck…changes should not be executed…until the second flight crew member has returned to the Flight Deck and a proper cross-checking and verification process can be undertaken.” Sorry, they just don’t trust you to do this by yourself, and neither should you!

Errors associated with re-clearances, re-routings and/or new waypoints continue to be the most frequent cause of GNE’s. Therefore, a re-clearance or amended clearance should be treated virtually as the start of a new flight and the procedures employed should all be identical to those procedures employed at the beginning of a flight.

- Both crews note the re-clearance

- Reply to ATC via ACARS or voice

- Amend the Master Document

- Load the new waypoints into the FMS from the updated Master Document

- One pilot verifies the input of the new waypoints reading from the FMS

- Verify the new tracks and distances, if possible

- Prepare a new plotting chart/re-plot in Jeppesen EFB

With datalink, you might have the capability to load the new route directly from the ATC message into your FMS flight plan. This will eliminate a transcription error on your part, but you cannot always count on the FMS to load this seamlessly. Oftentimes, if a revised coast-in waypoint doesn’t connect with your originally planned domestic airspace airway, it might cause a discontinuity. Worse, some crew have experienced their entire domestic flight plan drop out, left with only the oceanic portion.

Conditional Clearances – There’s always a catch!

A conditional clearance is an ATC clearance given to an aircraft with certain conditions or restrictions, such as changing a flight level based on a time or place. Conditional clearances add to the operational efficiency of the airspace, but are commonly misinterpreted by flight crews.

Shannon has been known upon first VHF contact to provide lateral conditional clearances on coast-in. For example: “N135AC, after DINIM, direct ELSOX”. Often, crew have been known to read back the correct transmission, but then execute the wrong procedure by proceeding directly to ELSOX.

Why is this happening? In studies of linguistics, verbs (such as ‘direct’) have been noted as having a perceptual priming effect, that more easily grabs our attention at the expense of weaker prepositions (such as ‘from’ or ‘after’). Listen carefully for prepositions. Similarly, in aviation vernacular, the word ‘direct’ means to proceed now to the specified waypoint. As pilots, we can distinguish this meaning with very little effort, and most of the time can expect to proceed present position direct. Thus, we are primed to go direct.

While this isn’t a complex sentence, research indicates that transmissions involving serial recalls (such as “proceed here then here…”) are susceptible to distortion, with the last word or item more commonly interfering with recall of the previous item.

A really simple way to prevent this is to write down clearances as they are being read to you, then read-back the transmission. You can also call attention to a conditional clearance by prefixing their read-back with the word “Verify” or “Confirm” over the radio. Via datalink, sufficient care always must be taken when factoring in all the contents of a clearance before acknowledging the message. The initial phrase “MAINTAIN FLIGHT LEVEL 300” is included to stress that the clearance is conditional. If the message is about to time out, and you need more time to process its contents, reply using “Standby”. Respond at your own pace![fancy_box box_style=”default” icon_family=”none” color=”Accent-Color” border_radius=”default” image_loading=”default”]

Cognitive Trap:

On the longer route segments between New York and Santa Maria, “when able higher” (WAH) reports might be solicited. ATC acknowledgement of a WAH report must not be misconstrued as a conditional clearance to climb. Any climb clearances will be issued separately from a WAH acknowledgement.[/fancy_box][heading]Miscellaneous[/heading]

10-minute Check – put the (Bad) Elf on the shelf for this

One of the best ways to capture a potential GNE and refresh your situational awareness is with the sublimely simple 10-minute check. Ten minutes after waypoint passage, you’ll use your current coordinates to plot your position on your plotting chart. If the coordinates don’t land on the plotted track line, an investigation into the source of the error must begin immediately. It doesn’t hurt to even make additional plots between waypoints too, but ICAO only requires the one 10-minute check.

Today, more pilots are carrying independent GPS units in their flight bags, providing crew with own-ship on their oceanic route map. Tempting though it may be to use this for present position information, it is currently not an approved source of navigation, and should NOT be used in lieu of a 10-minute check.[fancy_box box_style=”default” icon_family=”none” color=”Accent-Color” border_radius=”default” image_loading=”default”]

Cognitive Trap

It is easy to forget about the 10-minute check. Setting a timer once your waypoint passage tasks have been completed will help remind you to do so.[/fancy_box]

Autopilot mode – “Wait, are we supposed to be in heading?”

Incorrect autopilot mode selection has been known to be a factor in GNE’s. On an oceanic crossing, you can bank on being in NAV or LNAV most of the way across the Atlantic. But perhaps you used heading mode to deviate for weather or to intercept a SLOP. It is not uncommon among pilots to spare your passengers two steep banking turns (thanks LNAV!) by manually flying a SLOP intercept in heading mode. But if you forget to re-engage LNAV, you will continue drifting on your merry way, further and further off course.

Distraction, fatigue or complacency are common reasons for losing mode awareness, so the following simple tricks will help mitigate autopilot induced GNE’s.

- It helps to verbally announce when you are transitioning temporarily into heading mode, to bring both pilots in the loop.

- Employing sterile cockpit until you’re back in LNAV will help mitigate distractions.

- In an abundance of caution, you can keep a finger on the heading button or heading dial until you are back in LNAV will serve as a reminder.

[fancy_box box_style=”default” icon_family=”none” color=”Accent-Color” border_radius=”default” image_loading=”default”]

Cognitive Trap:

The flight mode annunciators (FMA’s) are the most reliable indicators of automation selection – more so than the flight guidance panel! Yet, a study found that pilots pay superficial attention to the FMA’s during critical mode changes. Don’t waste a valuable resource, and do consciously bring the FMA’s into your scan.[/fancy_box]Deliberate cross-checking and monitoring are a critical last line of defense for which we, as pilots, don’t get explicit training, but are nevertheless expected to perform effortlessly. But over the North Atlantic, there is little room for error. So, let’s recap what can be done!

- Allow sufficient time on the ground to set up

- Closely scrutinise data entry – whether the source is human or ACARS!

- Work together on waypoint verification

- Don’t work single pilot – always keep all crew in the loop

- Deal with clearances and re-clearances methodically

Understanding our vulnerabilities is key to the process of mitigating errors. Armed with an understanding of our own limitations, and an appreciation for the practices and habits mentioned above, a ‘would-be’ GNE can be averted.

Links

ICAO Doc 007

Global Operational Datalink Document (GOLD)

Nothing technical, just human.

Nothing technical, just human.

What happens in Danger Club? Top secret of course, but very simple: we get together as pilots to talk about

What happens in Danger Club? Top secret of course, but very simple: we get together as pilots to talk about