Volcanic ash has always been one of aviation’s most frustrating hazards. It is invisible to most onboard radar systems. It can cause engines to surge or flame out, and it can force huge reroutes with very little notice. Until now, forecast products have mostly shown where ash exists rather than how much of it is actually in the air. That is about to change.

The UK Met Office and Météo France are introducing a new type of volcanic ash forecast called Quantitative Volcanic Ash, or QVA. From 27 November 2025, QVA becomes an official ICAO product, with London and Toulouse the first VAACs to provide it operationally. More VAACs around the world are expected to join over the following year as the service is rolled out globally.

What QVA Is and Why It Matters

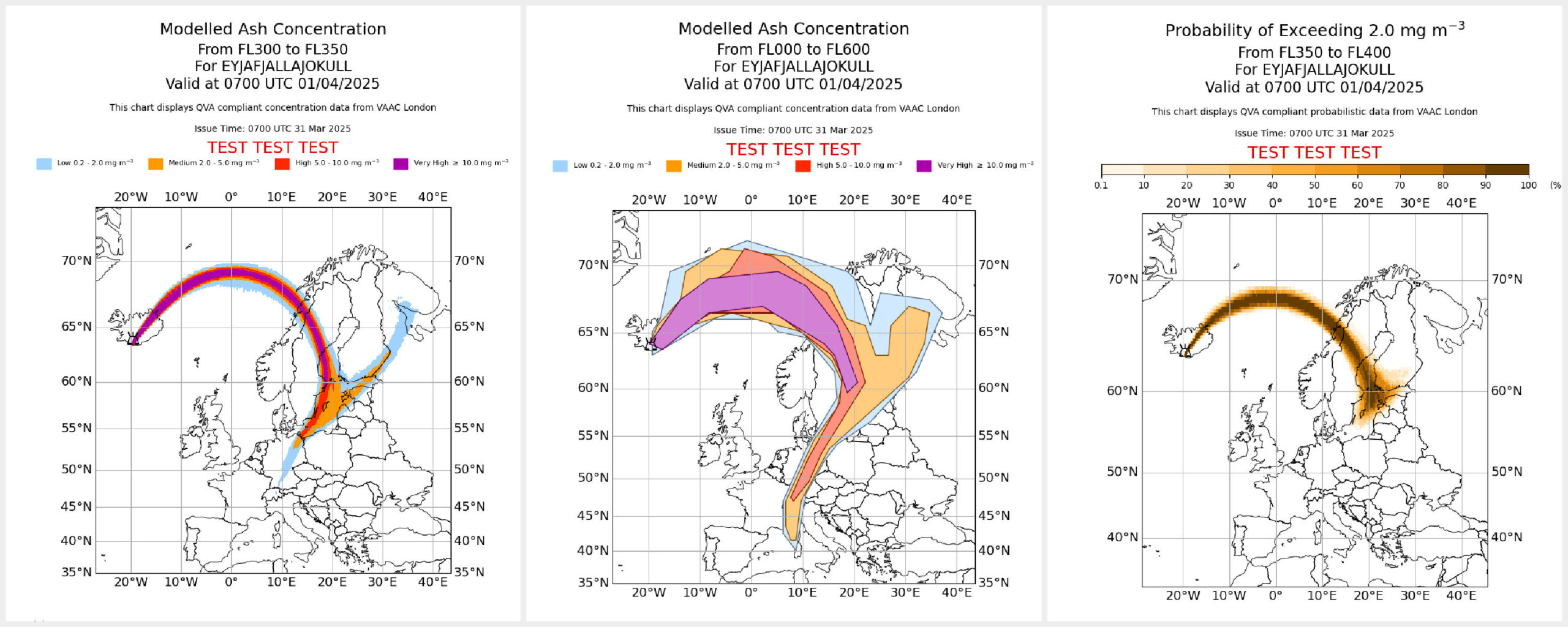

QVA gives you real ash concentration values at different flight levels. Instead of large shaded areas that simply show where ash might be, you get a detailed 3D picture of how much ash is expected in each place and at each time. This lets operators compare forecast ash directly with engine exposure limits rather than working with broad warning zones.

QVA also shows how confident the model is. Low uncertainty means you can keep margins tighter around an ash plume. High uncertainty means planning extra room into the route. It is a smarter and more practical way to think about volcanic ash when planning flights.

The forecasts have a much higher resolution than before. VAAC London says that one forecast used to take about an hour to produce. With QVA they can now generate around 150 ash fields in the same time. You get more detail and you get it faster, which is a big advantage in busy regions like the North Atlantic.

If the data is of interest to your organisation, a request can be made to VAAC London for access to their free QVA API. Just email QVA@metoffice.gov.uk with details of your organisational requirements for volcanic ash data across the north-eastern corner of the North Atlantic, including Iceland and the UK.

The API provides ash concentration and probability forecasts up to FL600 in 3-hourly time steps out to 24 hours, with new forecast runs issued at least every six hours while a significant ash cloud is a hazard. For more details you can visit the Met Office page, and you can also find additional QVA info from VAAC Toulouse.

In short, QVA looks like a real upgrade. Instead of staying far away from anything that resembles a volcano, we can finally make smarter and more precise decisions. Low concentration with low uncertainty may keep a flight close to its ideal track. High concentration with high uncertainty is your clear cue to reroute.

Ash will always be ash, but at least now we can be a bit clever about how we deal with it. We are curious to hear what you think, so we would love to hear from you at team@ops.group.

Volcanoes of the World: The Misery Tour

The last few years have given us a colourful mix of eruptions, each creating its own special brand of trouble for aviation. Here are a few highlights from our unofficial misery tour, in order from oldest to newest.

La Soufriere, St Vincent, 2021

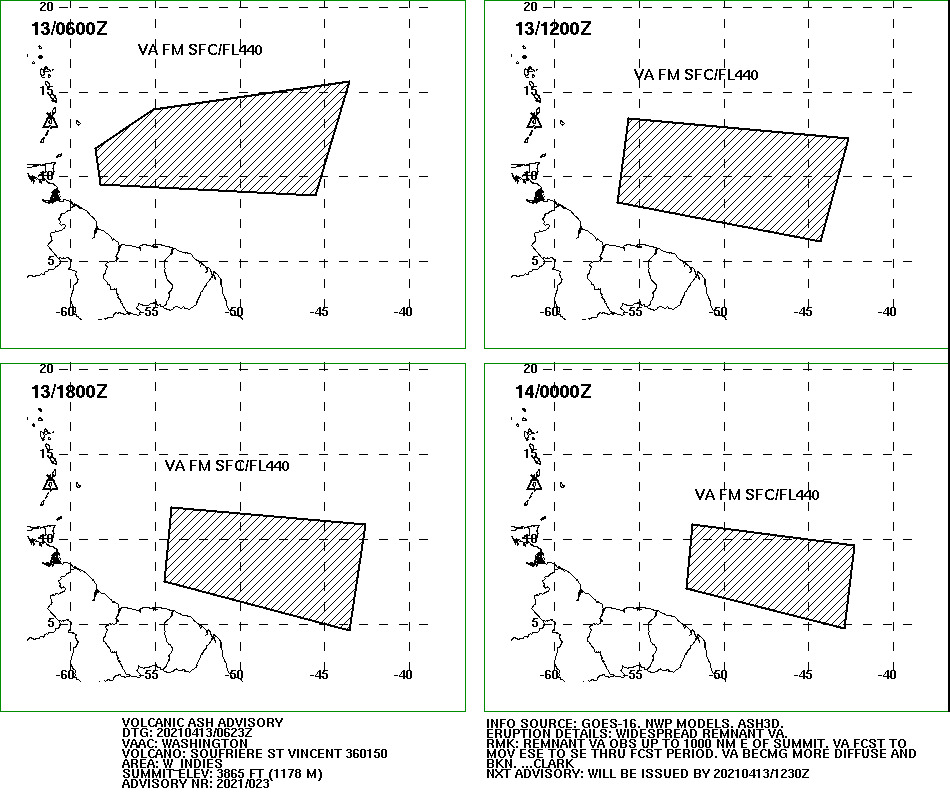

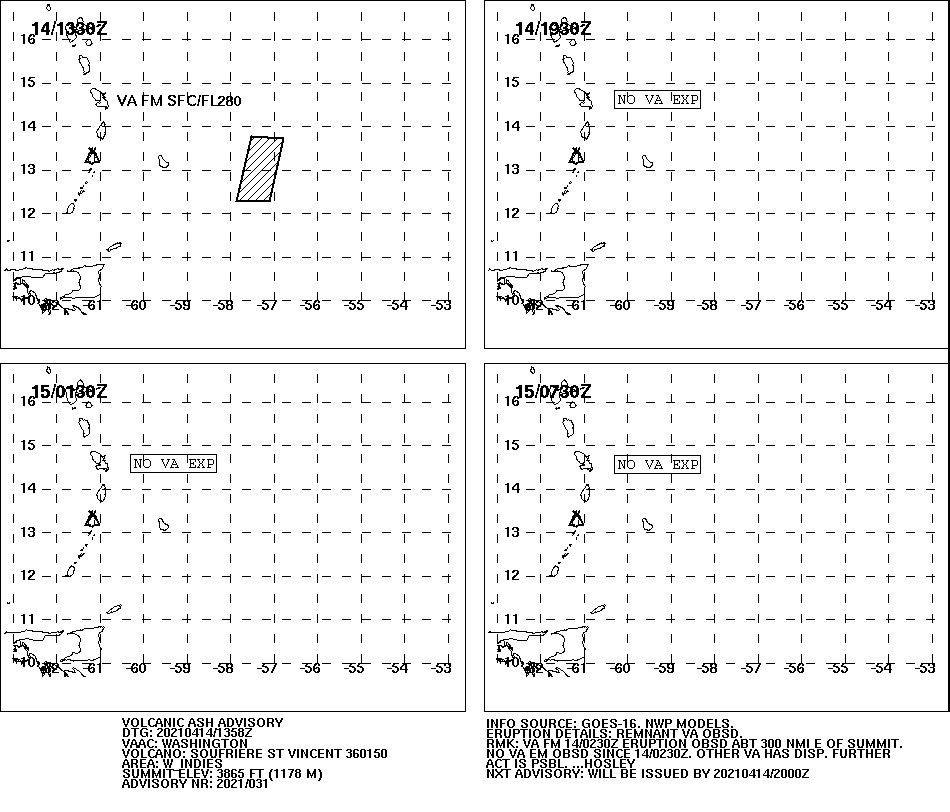

A run of explosive eruptions blasted ash up to about 40,000 ft and spread thick clouds across the Caribbean. Airports closed with little warning and alternates quickly filled up as crews diverted around the ash.

Most affected airports: TVSV/St Vincent, TBPB/Barbados, TGPY/Grenada, TAPA/Antigua

Hunga Tonga, Tonga: 2022

This underwater volcano delivered one of the biggest bangs ever recorded. The shockwave circled the planet, ash shot well above cruise levels and satellite links struggled under the pressure. Flights across the South Pacific had to reroute or delay until conditions improved.

Most affected airports: NFTF/Fua’amotu, NFFN/Nadi, NWWW/Noumea, YSSY/Sydney, NZAA/Auckland

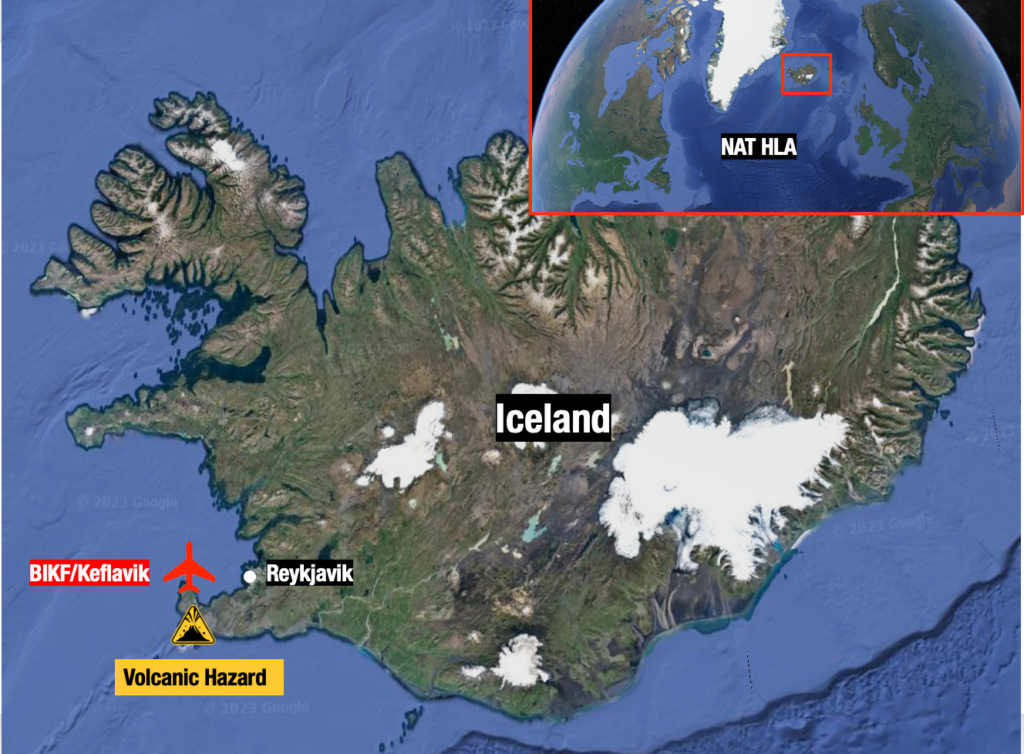

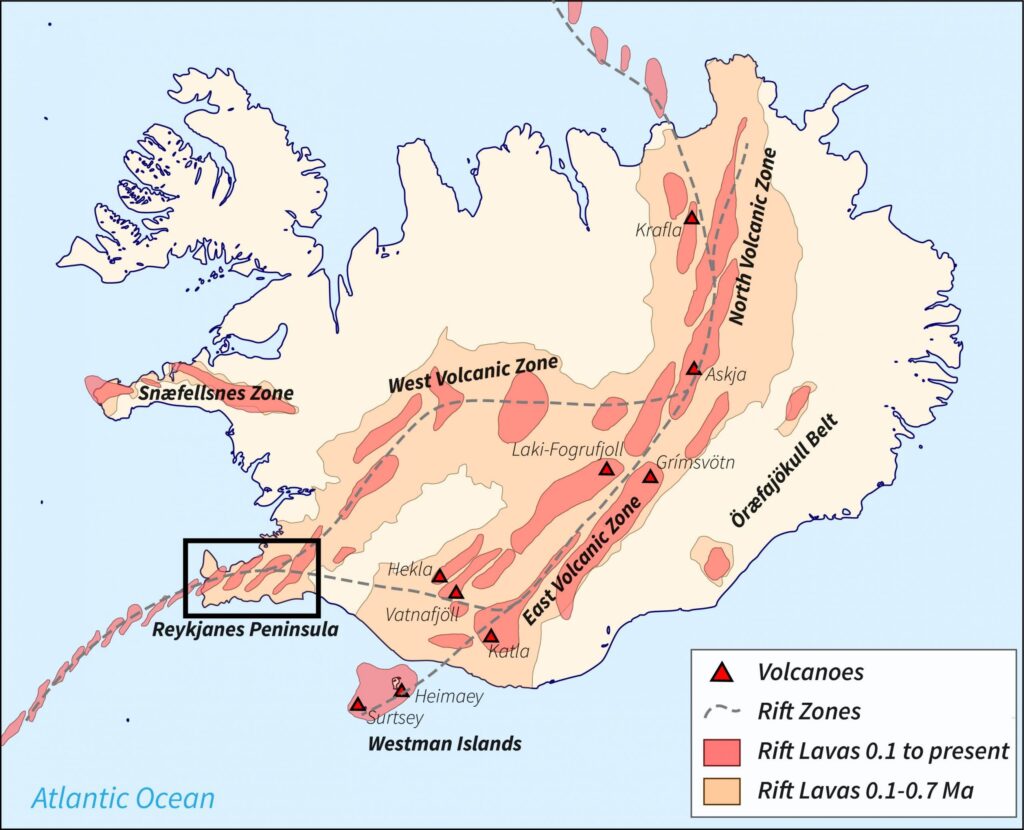

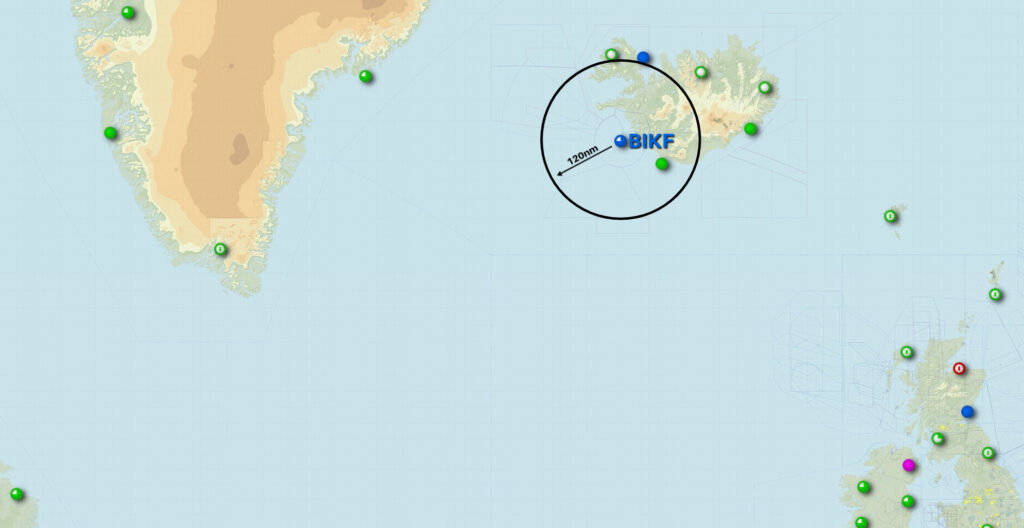

Icelandic volcanoes: 2023-2025

Activity around Fagradalsfjall and the Reykjanes Peninsula caused periodic airport disruptions and NAT flow adjustments. Nothing like 2010, but enough to keep everyone alert.

Most affected airports: BIKF/Keflavik, BIRK/Reykjavik, EGLL/Heathrow, EGKK/Gatwick

Etna and Stromboli, Italy: ongoing

Their eruptions are usually smaller but still a regular headache. Etna can reach flight levels and Stromboli occasionally pushes ash into southern Italian airspace.

Most affected airports: LICC/Catania, LICJ/Palermo

Sangay, Ecuador and Popocatepetl, Mexico: ongoing

Both erupt frequently and love throwing ash across busy Central and South American airways. Dispatchers in the region see SIGMETs from these two on a regular basis.

Most affected airports: SECU/Cuenca, SEQM/New Quito, MMMX/Mexico City, MMPN/Uruapan, MMTO/Toluca.

How Dispatchers and Pilots Actually Work With Volcanic Ash

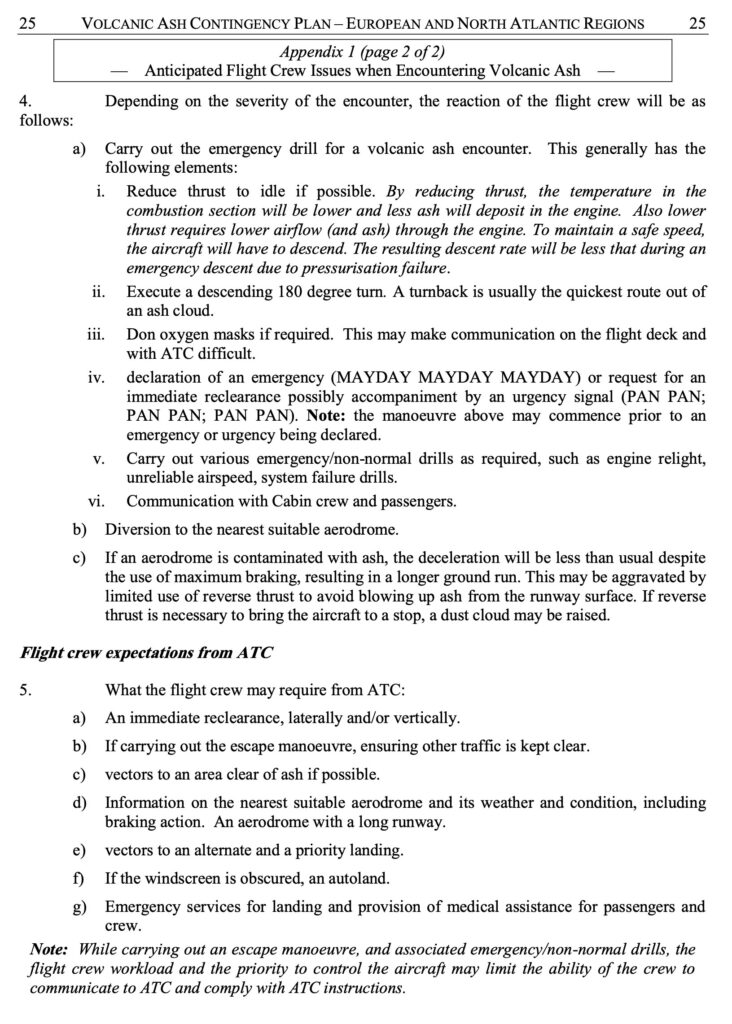

When volcanic ash shows up, dispatchers start with the big picture. The VAAC advisory outlines where the eruption is, how high the ash is being thrown and how the cloud is expected to drift over time.

For actual flight planning though, SIGMETs do most of the heavy lifting. They are the operationally binding piece because they identify where ash is present or expected within the FIRs you are about to cross and at which flight levels. If a SIGMET says ash is sitting between FL200 and FL350 along your route, that plan is getting a makeover. ASHTAMs then step in to describe the major operational impacts such as airport closures or significant service limitations caused by ash.

The routine is simple: check the VAAC to understand the overall structure of the cloud, check the SIGMETs to see what actually matters to your airspace and altitude, and then draw a route that stays sensible without being overly conservative. QVA will slide into this workflow neatly because it finally shows how much ash is out there and how confident the forecast is, which makes the whole decision process a lot more grown-up.

Ash is still ash, but at least now everyone can know exactly how worried to be.

What about you?

When you plan routes in areas affected by volcanic ash, what do you rely on most? Do you start with the VAAC advisories, or do SIGMETs and ASHTAMs carry more weight for you? How do you bring all these pieces together when deciding whether to reroute, change levels or continue as planned?

We would also love to know which tools, charts or sources you find the most useful in real ash events. Let us know at team@ops.group!

All traffic crossing the NAT or operating over Western Europe right now should be keeping a close eye on this one.

All traffic crossing the NAT or operating over Western Europe right now should be keeping a close eye on this one.