June marks the start of monsoon season throughout Southeast Asia. From now until October, enroute weather deviations will routinely exceed 100nm.

This creates a significant challenge for controllers and coordination between the high number of FIRs that span congested air corridors between Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Indonesia.

To make matters worse, the 2024 Monsoon season is predicted to be a bad one.

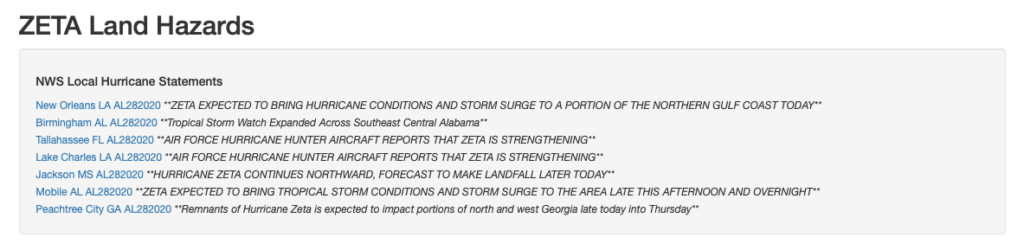

And so, the answer is something called Large Scale Weather Deviation Procedures (LSWD) already innocuously appearing in FIR Notams like the one below.

This raises two important questions:

- What does LSWD actually mean?

- What are operators doing about it?

In a nutshell, your standard contingency allowance may no longer be enough – meaning unfamiliar operators (especially on fuel critical routes) may unexpectedly be caught with their pants down.

So, let’s take a closer look.

The 2024 monsoon season is going to be bad.

The clever folk at the World Meteorological Organization recently said so.

Last year, in comparison, was weak.

You can take a look at their full report here, but the short story is that thanks to a spicy combination of ‘ninas and ninos’ much of Southeast Asia is about to receive up to ninety percent of its annual rainfall in the next few months. Which means large scale build-ups will be everywhere.

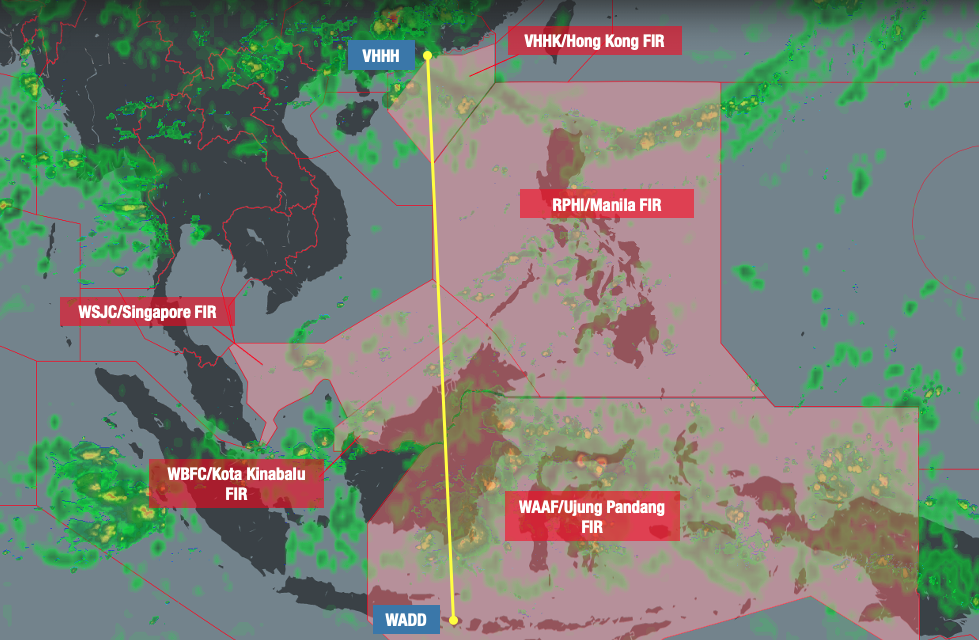

The airspace picture.

Spanning this area of unstable weather is a large number of adjacent FIRs serving some of the busiest air corridors in the world.

Take this routing (WADD/Bali to VHHH/Hong Kong) as an example, overlaid with current precipitation in the region. It’s very early days, but you can already begin to see the extent of the deviations FIRs are dealing with.

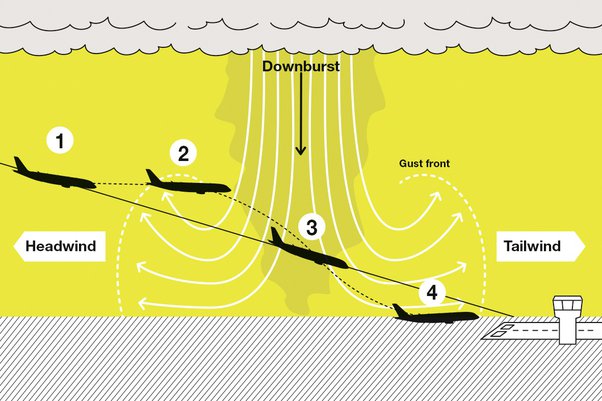

The sheer scale of weather deviations required by aircraft in this area creates a major challenge for air traffic control.

The lateral separation between adjacent airways is often far less than the deviation each aircraft will require, along with the narrower vertical margins of RVSM airspace.

This creates numerous problems for controllers – providing priority handling to one aircraft creates delays and disruptions for others. It’s your standard ripple effect.

To create room, ATC has specific protocols to manage these deviations. They call them LSWDs and they are used to reign in the mess.

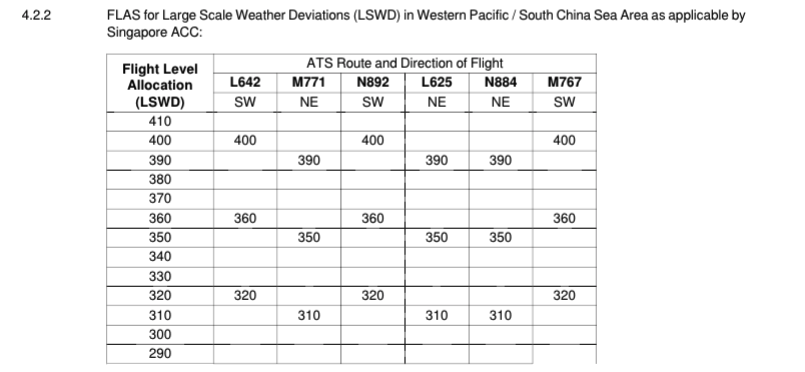

How do these procedures work?

Traffic will be processed through a limited number of routes with level restrictions bound by their direction of flight. These routes can be found in each state’s respective AIPs.

Here’s an example found buried in Singapore’s docs:

To make co-ordination easier between the numerous ATS sectors, all traffic operates with the same level availability whenever LSWDs are active.

To make co-ordination easier between the numerous ATS sectors, all traffic operates with the same level availability whenever LSWDs are active.

For business jets, this may become problematic as higher flight levels (FL400+) may not be available for extended periods of time.

As a locally-based G550 Captain explains:

“Even if higher flight levels are available in one FIR, controllers may be reluctant to give them to you. This is because there is no guarantee that the next sector can accommodate it and it can be hard to get you down again…

…The main thing with LSWD is knowing that a lot of levels we usually get won’t be available. And so, we carry more fuel accordingly. It may also be worth briefing the pax that conditions may be bumpier than they’re used to…”

Flow control and crossing time restrictions are also common which may mean the use of less efficient mach numbers.

This can also lead to delays for start-up clearances due to enroute spacing. When asked what additional fuel our local G550 Captain carries for these procedures, his answer was this – “at least thirty minutes.”

Have more to add?

Local operator feedback is invaluable to everyone in the group. If you’ve got anything to add to this article, get in touch with us at team@ops.group

Why does aviation hate them?

Why does aviation hate them? Satellites monitor storms as well, but mainly just send down horrifying photos of how massive they are.

Satellites monitor storms as well, but mainly just send down horrifying photos of how massive they are.