The other day, before another oceanic crossing, I settled in to brief myself on that afternoon’s flight plan.

As I scalded my mouth with a hastily purchased airport coffee and began to peruse the carefully collated collection of fuel burns and leg times, my eyes fell upon the dispatcher’s remarks. As I stared, the following note stared right back at me…

“Sorry guys, unavoidable EDR 60 at TOC…”

Apology accepted. But what on earth is EDR 60?

With the weight of the braid on my shoulder, multiplied by a factor of my stupidity as a proficient but highly ‘human’ aviator, I realised I needed to call in the big guns – this was a job for Google.

A powerful blankness ensued as I surveyed the answer… Eddy Dissipation Rate. The official metric of ICAO and World Met Organization turbulence reporting since I was in high school. Had I been living in a cave?

This thing mattered, and so I needed to dig deeper.

Here’s what I found out:

…it’s an aircraft-independent meteorological field expressed in meters squared per second cubed…

Not helpful. I read on…

…the cube root of the dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy…

I took another sip of coffee. I didn’t have time for this.

Sign-on was approaching, along with hundreds of passengers expecting me to protect them from this ‘EDR 60′ with my big fancy license. All I knew was that it meant bumps. Clearly, I needed to get a better grasp on this.

If you already know what EDR is, and could explain it to me on a napkin, there’s no need to read on. If you’re ‘asking for a friend,’ here is a crash course, written in human.

The Simplest Answer

You don’t need to cube anything. Except maybe the confidence you lost (like me) in not knowing what an EDR is. It’s pretty simple (ignoring the arithmetic of measuring it).

The higher the number, the more intense clear air turbulence may be…if you encounter it. Anything over 50 may result in moderate to severe CAT.

But that interpretation also depends on the type of aircraft you are flying.

So, there may be some nasty stuff around. But if you want to get your head around it, you’ll need to dig a little deeper.

So, let’s dig…

When we talk about turbulence, we refer to light, moderate, severe, and extreme. We attempt to categorise these with useful definitions like ‘loss of control.’

The problem is that it is quite challenging to quantify the severity of CAT concerning different aircraft types – what’s bad in a 152, may not be as bad in a Gulfstream. It varies from aeroplane to aeroplane, and forecasters don’t know what equipment you operate.

This is where EDR comes into it – it doesn’t cares about what aircraft you fly. It is just a measure of something.

An eddy is simply the swirling of fluid. And air behaves like a fluid. A turbulent atmosphere will make these eddies disappear quicker. A calmer one will allow them to persist.

So, if we know what is happening to these eddies, it can give us an indication of how ‘churny’ the atmosphere is, along with a healthy dose of mathematics, of course.

Eddies dissipate quickly = a turbulent atmosphere.

An EDR is measured with a value of between 0 and 1. But seeing a value of 0.4 for instance, doesn’t exactly leap off the page of your flight plan.

So, we multiply it by a factor of 100 to make it easier to use.

Cool, we’re almost there…

One size doesn’t fit all

Once we have an EDR, we must know what to do with it.

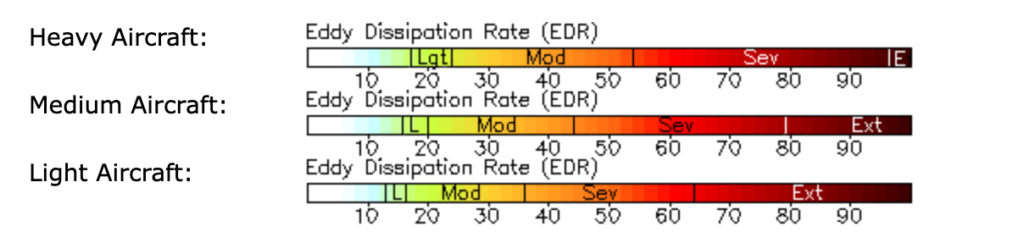

As mentioned, every aircraft is different and will respond differently to turbulence. This is where weight begins to matter.

An EDR of 20 might produce moderate turbulence for a King Air, but gently shake the champagne glasses of an A380 and nothing more.

The clever folk at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, therefore did a study and came up with three weight classes to help you understand an EDR:

Where do I find this EDR?

Many non-airline folk don’t have the luxury of a friendly dispatcher like I had.

But you can quickly look it up. Better yet, it is as simple as paint by numbers (if you know what to do with the answer).

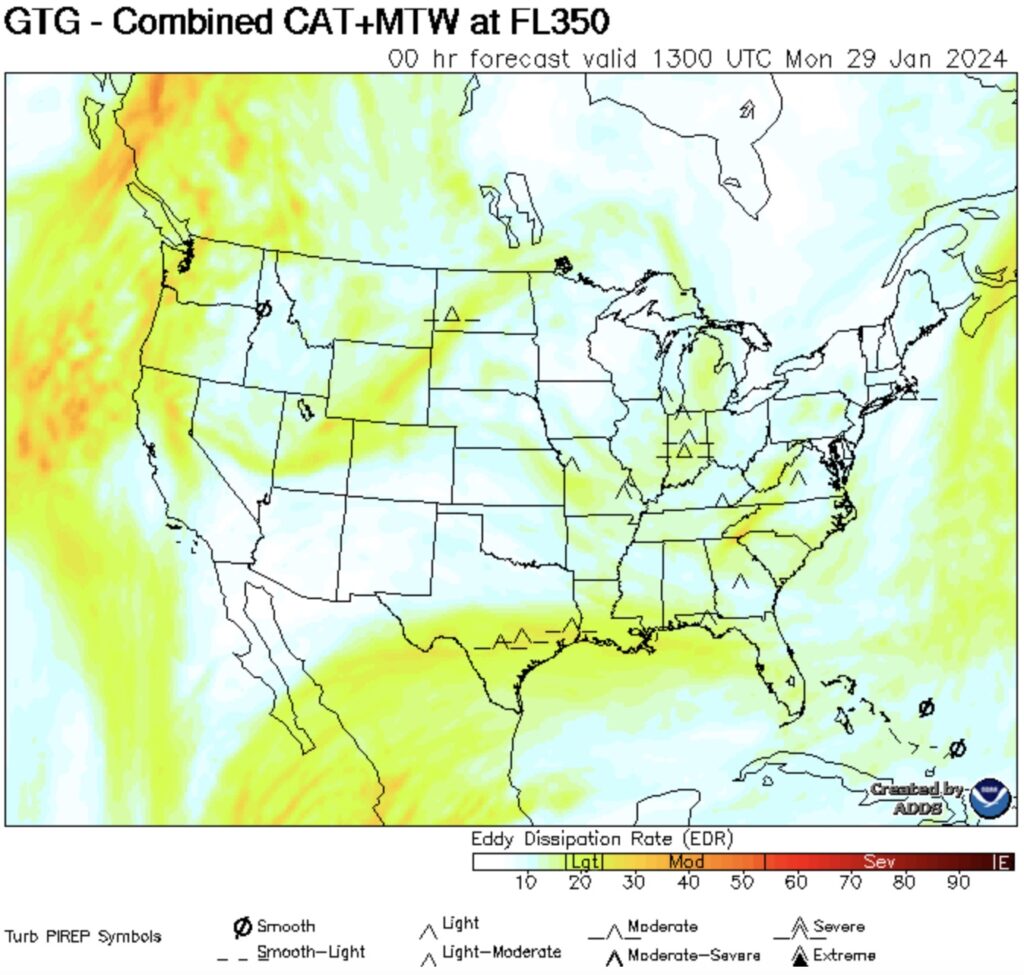

It would help if you had GTG (graphical turbulence guidance) like the one below. And the colours change depending on how heavy your aeroplane is.

Better yet, the way EDRs are presented can be changed. For instance, cross-sections of a route can also give pilots a good indication of the smoothest levels.

Check out the NOAA website here.