Key Points

- TIBA still seems to be an issue in Australia – shortage of ATC resulting in big bits of restricted Class G airspace, often at short notice.

- We wrote about this last year, including guidance on what to do (see updated post below), but now IFALPA have published a Safety Bulletin saying the problem is still ongoing.

- Amid accusations of understaffing, Australian ATC has announced they intend to strike. This process will take a few weeks to action, and so we’ll likely see disruptions from May. This may include full 24hr work stoppages and will be notified in advance via the YMMM/Melbourne and YBBB/Brisbane FIR Notams.

Since early in 2023, we’ve seen large sections of restricted TIBA airspace (traffic information broadcasts by aircraft) established by Notam up Australia’s East Coast in both the YMMM/Melbourne and YBBB/Brisbane FIRs.

In fact, there were 340 instances of uncontrolled airspace between June 2022 and April 2023 alone. And it’s still happening.

The cause here appears to be a fundamental shortage of air traffic controllers.

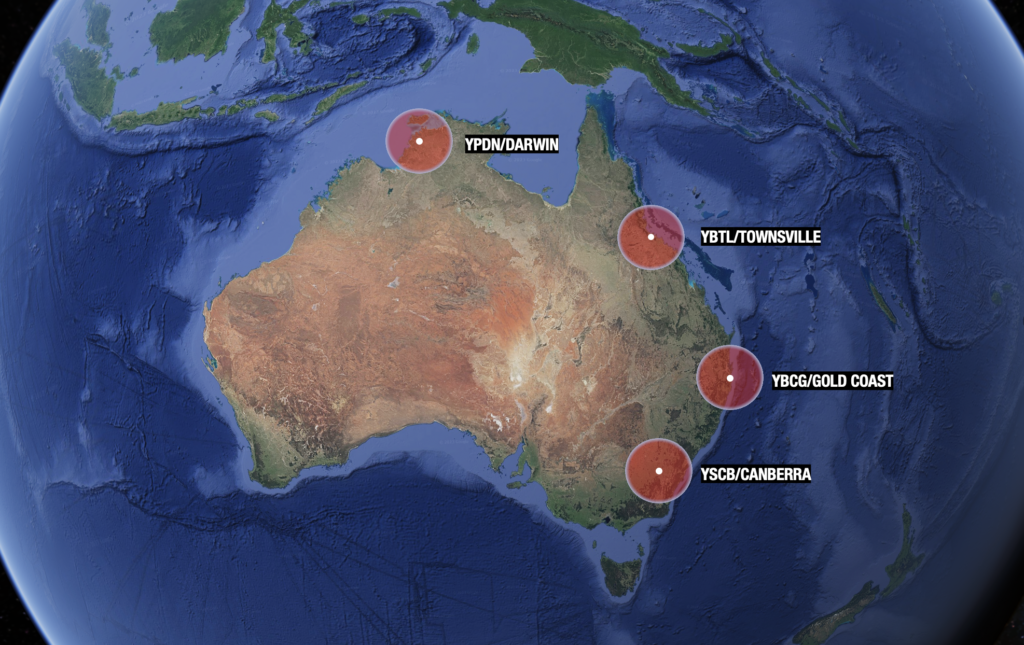

Where has this been happening?

In the South, look out for TIBA airspace east of YSCB/Canberra airport, Australia’s capital city found inland from Sydney.

Further north there has been a greater effect as large portions of coastal airspace near YBCG/Gold Coast and YBTL/Townsville airports have been impacted. This is an extremely busy air corridor – 80% of Australia’s population live on the East Coast.

At the top end of Australia, YPDN/Darwin airport has also been affected which can result in re-routes for international traffic headed up into South-East Asia and beyond.

Here’s what those hotspots look like on a map:

TIBA airspace has been reported in or near these hotspots.

It’s not all the time.

TIBA airspace is being activated by Notam, typically for hours at a time. A look at today’s batch indicated all is ops-normal. However, a local airline captain has advised OPSGROUP that it is currently a frequent occurrence.

Broadcast, or avoid?

The vast majority of airline traffic appear to be avoiding the TIBA airspace. This typically involves less direct routes at the expense of delays and fuel. Helpfully, for major city pairings the NOTAMs contain suggested routes that will keep you clear. But expect SIDs or STARs you may be less familiar with.

In fact, major carriers have policies in place that prevent them from using TIBA airspace anyway – unless they happen to be in it when it is activated.

That’s not to say there won’t be other traffic taking advantage of the more advantageous routes though. The East Coast is characterised by a huge variety of traffic including charter, skydiving, medevac and survey all of which may have valid reasons for using TIBA.

It can still be used safely, but with the procedures below (a heads up: dual comms are a requirement).

How on earth do I ‘do TIBA’?

First things first. Whatever you do, don’t enter without permission. Australia’s TIBA airspace is typically restricted – in the sense you will need PPR to use it. The relevant Notams are quite helpful, and provide all the information on how to get it. Here’s an example.

Your approval will typically involve a phone call beforehand, and a chat to a flight information service in adjacent airspace for traffic information.

Once you’re in, you are totally responsible for terrain and collision avoidance. Turn that radio up and make sure you’re both alert and monitoring both the TIBA frequency and the relevant ATS one – now is not the time for controlled rest. Whoever is on the radios is going to be busy.

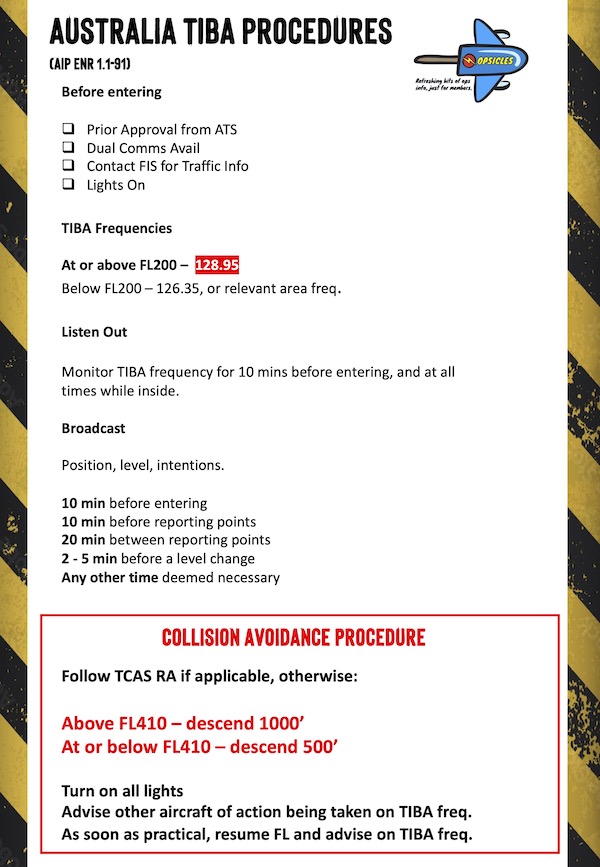

The Australian AIP then takes over. You can find the procedures in full here (time saver: flick to ENR 1.1-91). We’ve also put together a summary of those in this handy little briefing card which may be useful to keep in your flight bag:

Other questions?

You can also get in touch with CASA via this link, or alternatively Airservices Australia here with questions. Both have been very helpful in answering our pesky conundrums in the past.