Change is in the stars, literally.

Cheaper launch costs, reusable rockets and the world’s insatiable appetite for space based technologies have dangled a cosmic carrot for private enterprise to make money in space. The commercial space industry is booming. It turns over hundreds of billions of dollars each year and will hit the trillions by 2040.

This means more launches and re-entries than ever before as demand for earth’s lower orbit soars. In the US alone there have been sixty-five licensed commercial launches since the start of last year shared among twelve different launch sites – that’s a lot of rockets.

Space is also the realm of the billionaire visionary. Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic aims to soon make space tourism a reality. Over at Space X, Elon Musk dreams of colonizing Mars while Jeff Bezos seeks to inhabit our moon. Ambitious plans are on the horizon.

We’re on a Collision Course

The problem for commercial aviation is that the space industry needs our airspace more than ever. There’s no other way to the stars than straight through it.

Unless we find new and more efficient ways of sharing it, an increasing burden will be put on aviation to accommodate more and more launches in our skies.

The cost will come in more time, more fuel and more emissions.

Here’s the problem.

Space launches used to be a pretty rare occurrence. Across its career, the Space Shuttle for instance averaged only five launches each year.

Procedures haven’t changed a great deal since then either. When a rocket is launched, large chunks of airspace are closed for long periods of time. And once it’s all over, everything gets reopened. Safe right? But practical?

Not really, when staring down the barrel of hundreds of launches per year.

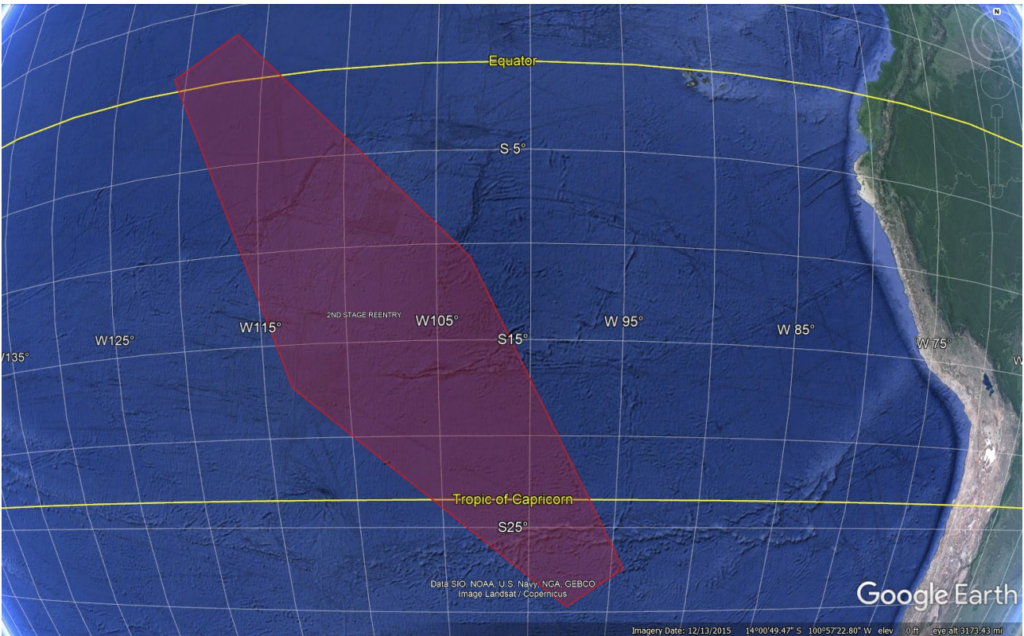

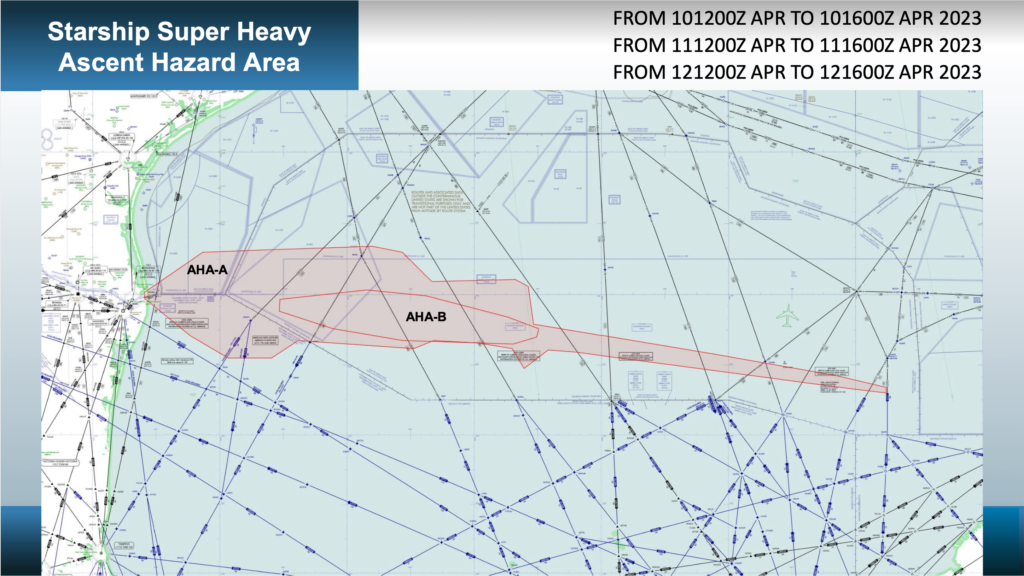

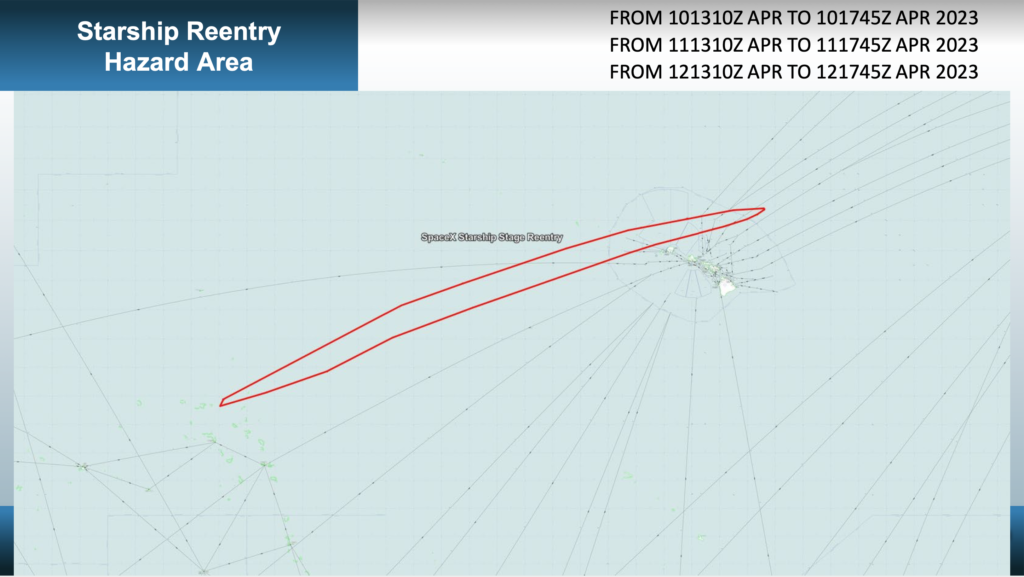

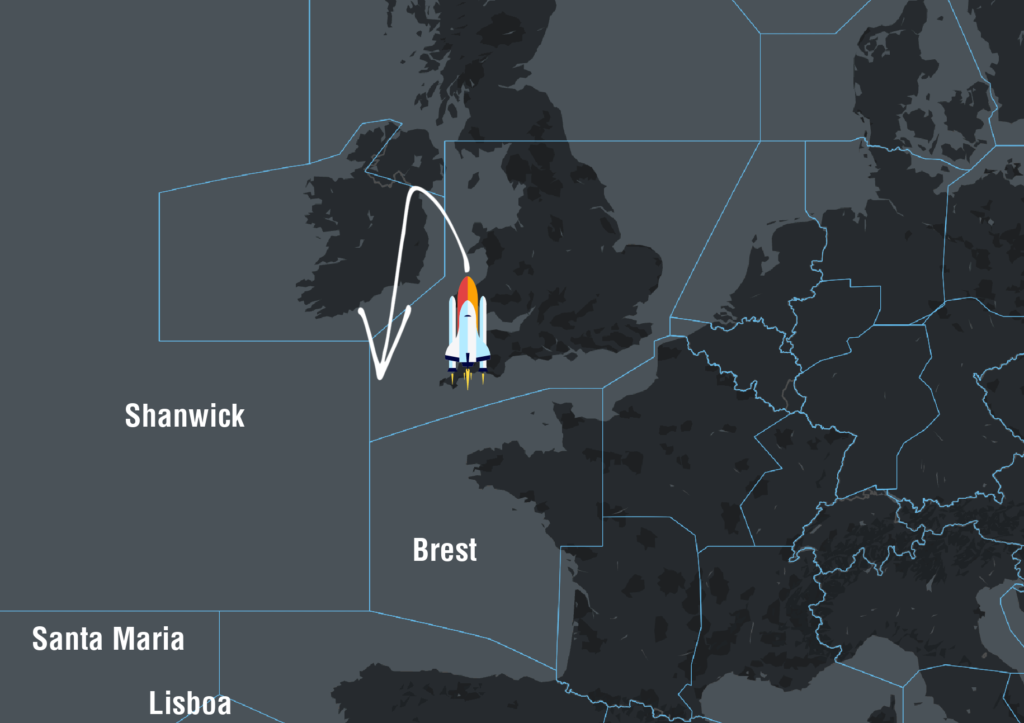

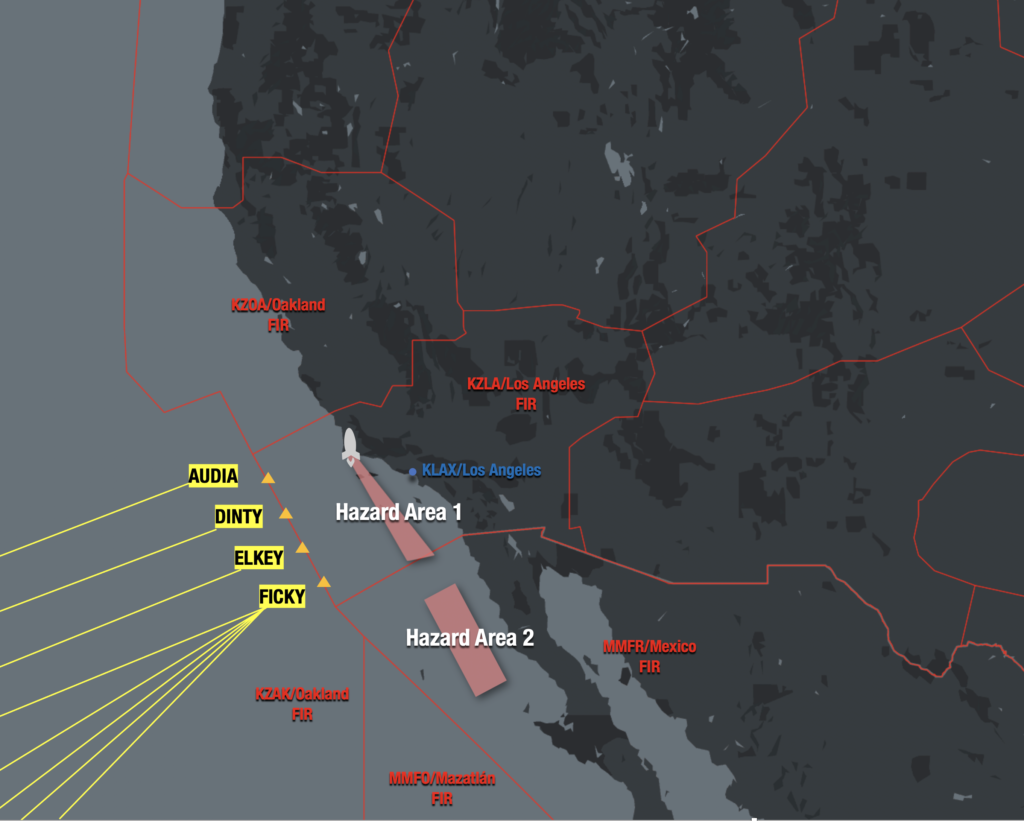

Take the US for example. The majority of launch sites are located on the coast and affect oceanic airspace. When you factor in the type of launch vehicle, its trajectory, where it will go if it needs to abort, where its boosters will land and any other hazards the airspace closures quickly become huge.

Launch sites in California affect Pacific routes. A single mission can affect half of the airspace between Hawaii and the West Coast. Launch sites in Virginia and Florida affect North Atlantic routes and lead to congestion in other airspace, such as Jacksonville.

Launch windows are also hours long, with backup windows in case of poor weather.

A famous Space X launch back in 2018 is a great example. You might remember the one – it delivered a small red Tesla Roadster to space in the very first test launch of the Falcon Heavy rocket.

Its launch window was open for two and half hours. Due to unfavourable winds, it used up most of that. In the meantime, the FAA couldn’t re-open the airspace above it.

While the world waited for a ten minute launch, 563 flights were delayed and 34,841 extra miles were flown. 5,000 square miles were affected resulting in cumulative delays of seventy-seven hours.

That’s an expensive ride to space.

What’s the solution?

ALPA suggested that the current approach is based on segregation – keeping airplanes away from rockets. But the future relies on integration.

In a nutshell, here’s what they suggest to make it happen:

Better Comms.

Broadly speaking, spaceflights need to be operated using similar procedures to how we manage earth-bound traffic.

Just like flight plans, launch plans could be introduced with similar details which can be communicated to all other airspace users and controllers in real time and amended when disruptions inevitably happen.

Existing technology used for remote or oceanic airspace can help here too. Fancy things such as next-gen HF and datalink could be used for live communication between pilots, air traffic control and space operators.

Better Surveillance.

It’s already on the way. The FAA’s Space Data Integrator is a huge step forward in automating and simplifying the flow of live launch and re-entry data so that areas of risk to aircraft can be more efficiently predicted. The project has global potential.

Space-based ADS-B is another opportunity. Already making a big impact over the NAT, it could also be used for spacecraft, including their boosters during re-entry to help air traffic controllers manage airspace closures far more efficiently.

Better Sep.

With technology leading the way, we can begin to safely reduce the margin between aircraft and spacecraft. New international standards would need to be developed to make this happen – and both industries would need to be onboard.

With all these launches, what about debris?

Are we actually at risk?

The uncontrolled re-entry of debris from China’s Long March 5 rocket raised a few eyebrows (including NASA’s) a couple of weeks back when it splashed down east of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean.

For several days no one could say for sure where or when it would re-enter, making the issue of accurate aviation warnings impossible.

The launch and re-entry phases of space flight are usually protected by airspace restrictions designed to keep us well away from anything that could go boom. And unlike anti-aircraft weaponry designed to actively seek out aircraft, space-bound rockets only present a ballistic risk – in other words, being in the wrong place at the wrong time. But this is solved by closing airspace.

Space debris is another danger, albeit a tiny one. It poses far more danger to people on the ground that it does to us up in the air. Admittedly there is a bunch of it up in orbit – 170 million pieces to be precise, but the US Government estimates that only about 400 of them re-enter each year. That’s about one per day.

A recent study actually crunched the numbers. The chances of a single piece of space debris (such as that from China’s Long March 5) hitting an aircraft is somewhere in the realm of a tiny fraction of a percent. That’s not to say it can’t happen – back in 2007 an A340 operating over the South Pacific came uncomfortably close, but the odds of a direct hit are almost zilch.

So far more pressing right now is how we fit two industries into one sky.

The sky’s the limit.

NASA and the FAA have an MOU regarding spaceflight, where they have committed to working together to improve safety and integration between space and earth based operations.

The FAA have also recently announced new symbols on their navigation charts, showing launch sites for better pilot awareness. Your first point of call remains the published TFR list, and notams regarding launch windows.

The potential benefits of commercial space travel are huge. But practically speaking both industries need to keep working on better and more efficient ways to share airspace. Otherwise we are all headed for one heck of a traffic jam up there.

Several airways off the coast will be impacted – primarily for those running north and south between the mainland US and Southern Mexico. Major ones include L207, L208, A766, A770, L214, and L333 impacting boundary waypoints IPSEV, DUTNA, KEHLI, IRDOV and PISAD between the KZHU/Houston Oceanic and MMFR/Mexico FIRs.

Several airways off the coast will be impacted – primarily for those running north and south between the mainland US and Southern Mexico. Major ones include L207, L208, A766, A770, L214, and L333 impacting boundary waypoints IPSEV, DUTNA, KEHLI, IRDOV and PISAD between the KZHU/Houston Oceanic and MMFR/Mexico FIRs. Mission Accomplished

Mission Accomplished

South of the Equator

South of the Equator