Read all about it! ICAO are changing up the NAT docs!

Here, for you, is our summary of the *exciting amendments to our *favourite documents.

*They aren’t that exciting. Also aren’t our favourites, clearly that is 007.

First up, Doc 008

NAT Doc 008 ‘Application of Separation Minima North Atlantic Region’ contains exactly what the title suggests: info on the application of separation minima. The standards that it doth contain apply to aircraft in the NAT Region who are communicating via a radio station or via CPDLC and also when in ‘Direct Controller Pilot VHF voice Communication’.

Excellent. We saw an amendment notification and we headed over to see what the change was. With baited breath we clickethed upon the link. Fingers tapping as it slowly downloaded itself and opened. We scrolled with frantic enthusiasm to the ‘amendments’ table. What would the change be? Is it big? Is it exciting?

They have just amended paragraph 3.4.2.D to say that longitudinal separation is ‘10 minutes between aircraft on same/intersecting tracks, whether in level, climbing or descending flight, provided the aircraft have ADS-C periodic contracts with a maximum reporting interval of 20 minutes or are being tracked by an ATS surveillance system.’

‘or are being tracked by an ATS surveillance system’ appears to be the only change, at least that we can see anyway.

Doc 006

This one looks more interesting. First up, a review of what Doc 006 is.

In case you aren’t familiar with this one, it used to be:

- Part I – Contingency Situations Affecting ATC Facilities

- Part II – Contingency Situations Affecting Multiple FIRs

- Now it has Part III – Contingency Situations Caused By Space Weather Events, which ‘considers events which are likely to affect one or more than one facility within the NAT region, specifically the contingency processes applied to minimize operational impacts of space weather events.’

You can find the updated Doc 006 parts here.

Part I of Doc 006 – Air Traffic Management Operation Contingency Plan.

The only change in this bit is the insertion of some text onto Page 1 about Part III – The Space Weather Contingencies.

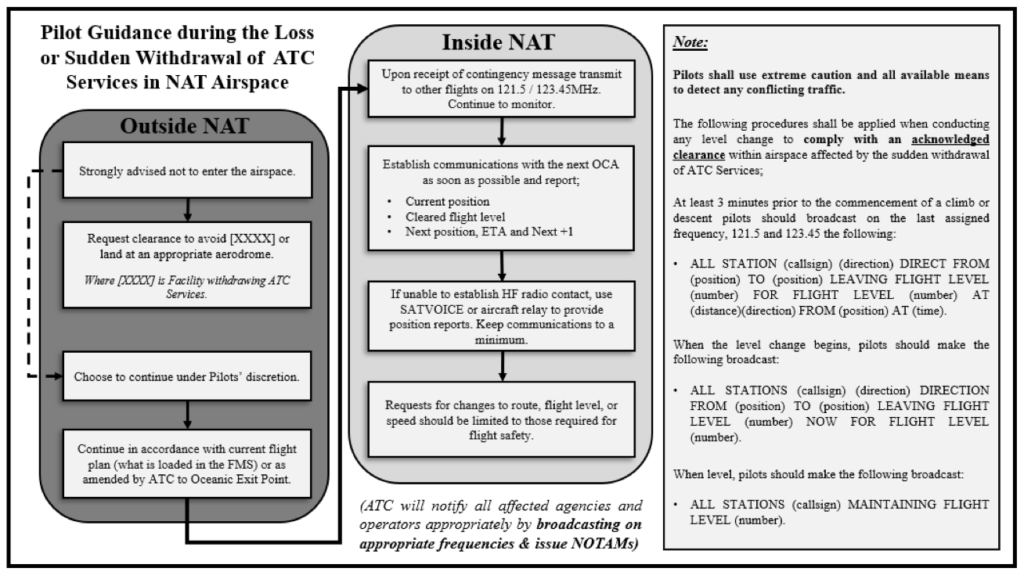

There is also this newly amended table which, while grey and joyless, is actually very handy indeed. This covers general loss of ATC which could be space weather related, but could also not be space weather related.

Simple but mighty.

Doc 006 Part III

I’ve given it a section of its own. This is the Space Weather bit, but, there is an actual document – Doc 10100 – which talks about space weather. 10100 can be found here and this is where you should go for *all your space weather knowledge needs.

*Not all, but a good start.

Doc 006 Part II is all (only) about the contingencies in the event of issues with ATC, navigation, systems etc because of space weather.

A little bit of space weather info before we dive all the way in:

Space weather can play havoc on our GNSS systems, satellite stuff, HF, RF, power grids, even our microwaves (microwave links whatever they be). It can also have effects beyond just one FIR, or even the whole NAT region. So it’s a great thing that we now have a document to help.

Don’t fly too close to the sun

Space Weather peaks around every 11 years, but we’ve seen a load of pretty decent (but not severe) space weather stuff of late. Things like:

- Disruptions and even total unexpected loss of HF, SATVOICE, CPDLC etc

- Issues with GNSS (that impacts out ADS-B and C)

- Weird and random reboots of electronic stuff onboard

- Passengers and crew growing extra limbs/glowing green etc

The Contingency Phases

They’ve broken the actions down into a few phases.

Initial Action (Reactive Phase):

What is happening during this phase is some space weather is whizzing its way over and an ANSP has become aware of it and so they start telling everyone about it, putting contingency plans into action, getting in touch with other ANSPs for support etc.

If you’re an airplane that is not yet in the NAT region then the general plan is to warn you about what might be awaiting you, and possibly (if it is really bad) re-route you.

If you are already in the NAT then you should do what you would normally do if you lose comms, or have some technical issue and that’s follow the published contingency procedures.

Subsequent Action (Proactive Phase):

What is happening in this phase depends on the severity of the situation, but basically a whole load of communication (about the severity of the situation) and stuff to help manage it.

Long term contingency plans:

This is for the really bad stuff that knocks out comms or satellites of what have you for really long amounts of time.

That… wasn’t very helpful

Doc 006 is really just more of an outline of what ATC will do (and so what the pilots can expect).

So, refer to the nice table, refer to the AIPs, go read your actual contingency procedures, and use this Doc 006 Part III as a helpful guide on what to expect.