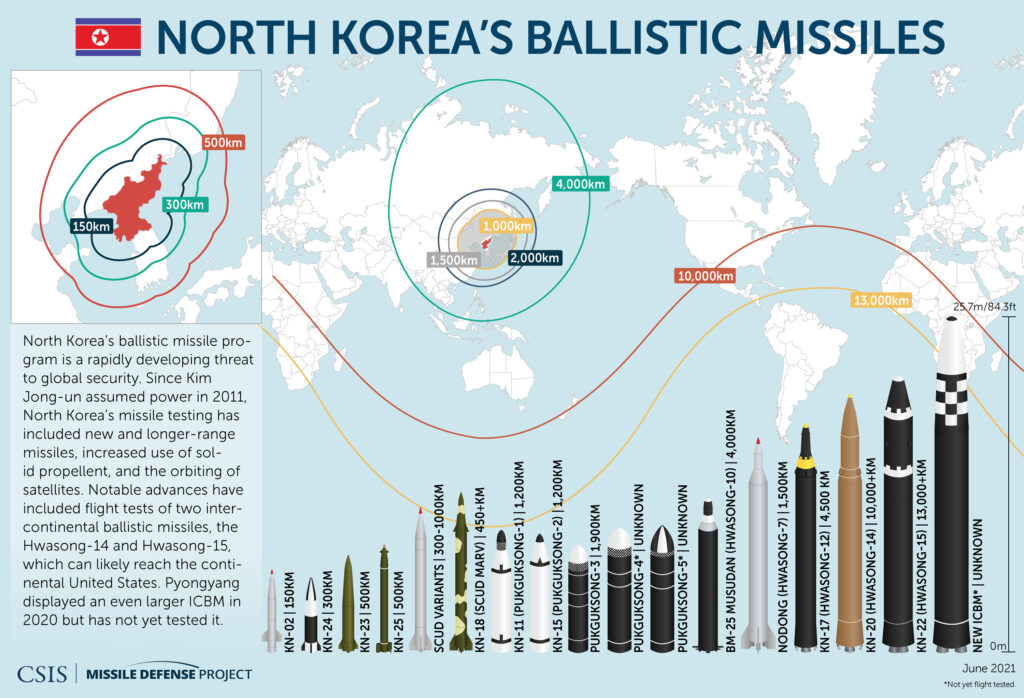

North Korea fired two short-range ballistic missiles across its east coast and into the Sea of Japan on Sep 15. It was North Korea’s second weapons test in recent days, after the launch of a new long-range cruise missile at the weekend, which state media claim has a range capable of hitting much of Japan.

North Korea has in the past tested intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) said to be capable of reaching nearly all of the US mainland and western Europe.

UN sanctions forbid North Korea from testing ballistic missiles (the ones that go up into space and then back down again, spraying debris all over international airways), but not cruise missiles (the ones that fly at low altitudes).

UN sanctions forbid North Korea from testing ballistic missiles (the ones that go up into space and then back down again, spraying debris all over international airways), but not cruise missiles (the ones that fly at low altitudes).

As usual, North Korea did not provide any warning prior to these recent tests – which is the key issue with regards to the airspace safety risk.

A quick history of developments in the last few years:

- Until around 2014, North Korea notified ICAO of all missile launches, so that aircraft could avoid the launch and splashdown areas.

- In 2015, they gradually stopped doing this, reaching a point where there could be no confidence in an alert being issued to airlines by North Korea.

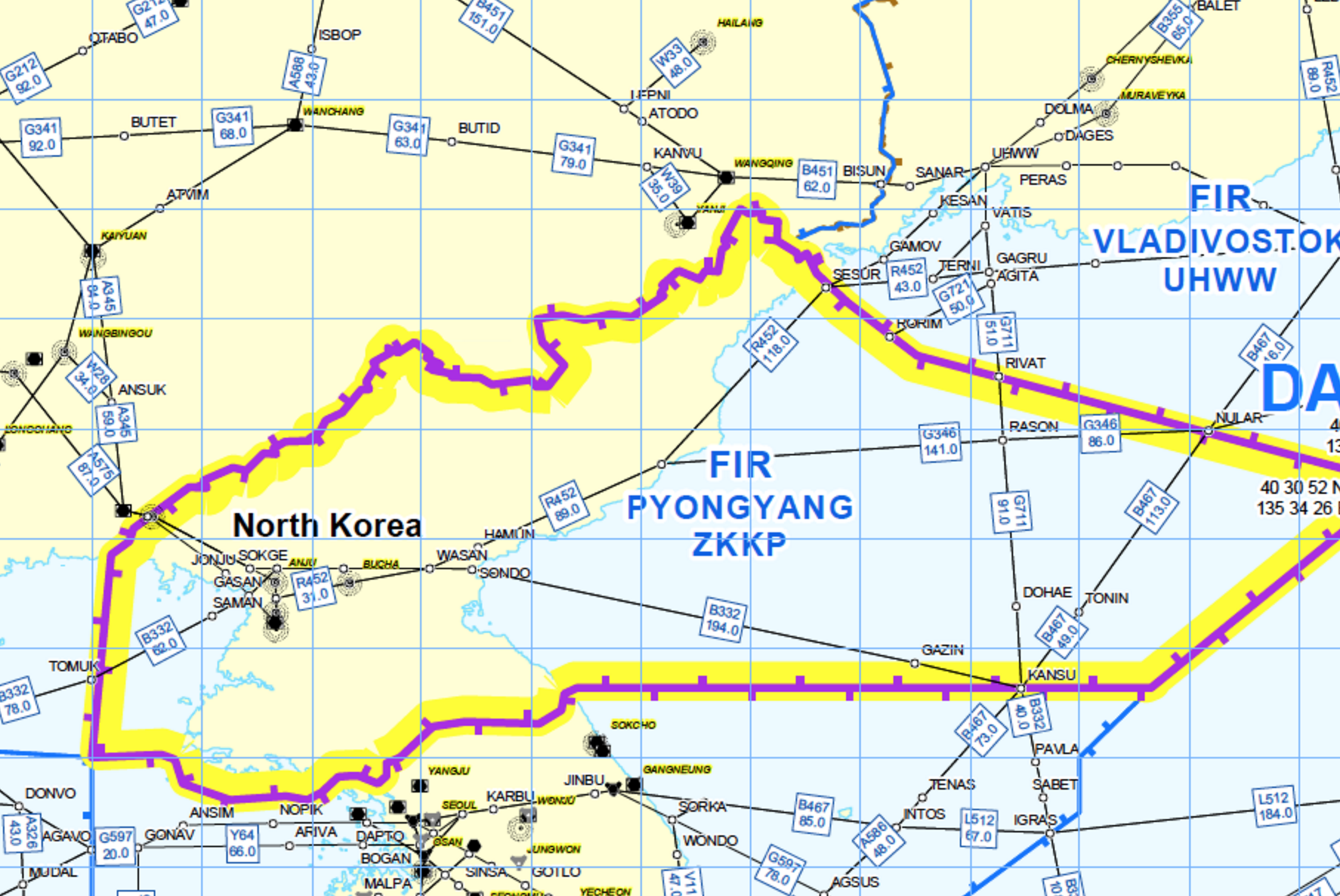

- In 2016, airlines and aircraft operators started avoiding the Pyongyang FIR entirely, by the end of 2016 almost nobody was entering the airspace.

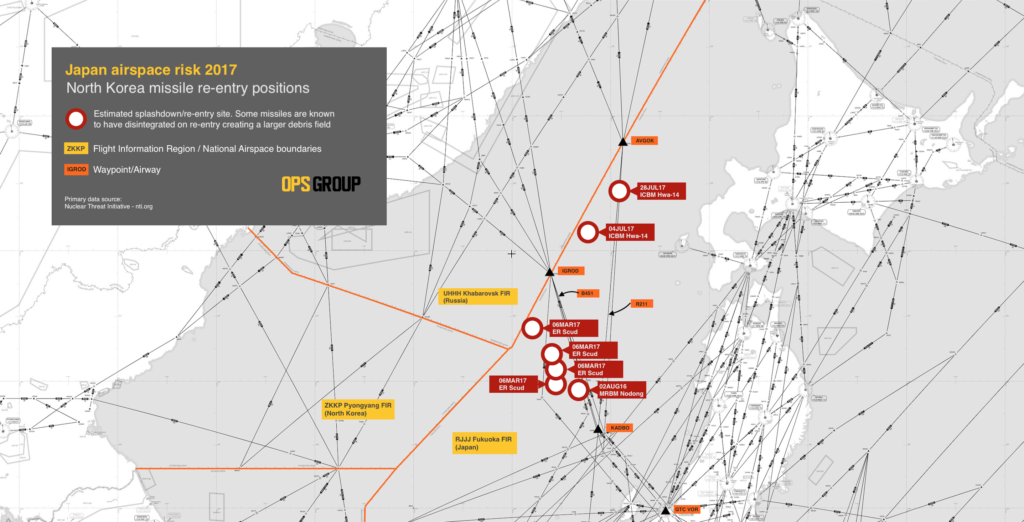

- In 2017, more and more of these missiles came down in the Sea of Japan, increasingly closer to the Japanese landmass. OPSGROUP researched the locations and produced a map of the risk area, together with the article: “Here’s why North Korean missiles are now a real threat to Civil Aviation”. In September 2017, the US announced a ban on flights across all North Korean airspace, including the oceanic part of the ZKKP/Pyongyang FIR over the Sea of Japan. That ban is still in effect today. Several other countries have airspace warnings in place which advise caution due to the risk posed by unannounced rocket launches.

- In 2018, following talks with the US, North Korea agreed with ICAO that it would provide adequate warning of all “activity hazardous to aviation” within its airspace.

- In May 2019, North Korea resumed its practice of launching missiles into the Sea of Japan without providing any warning by Notam.

Determining risk

The critical question for any aircraft operator is whether there is a clear risk from these missiles in the airspace through which we operate.

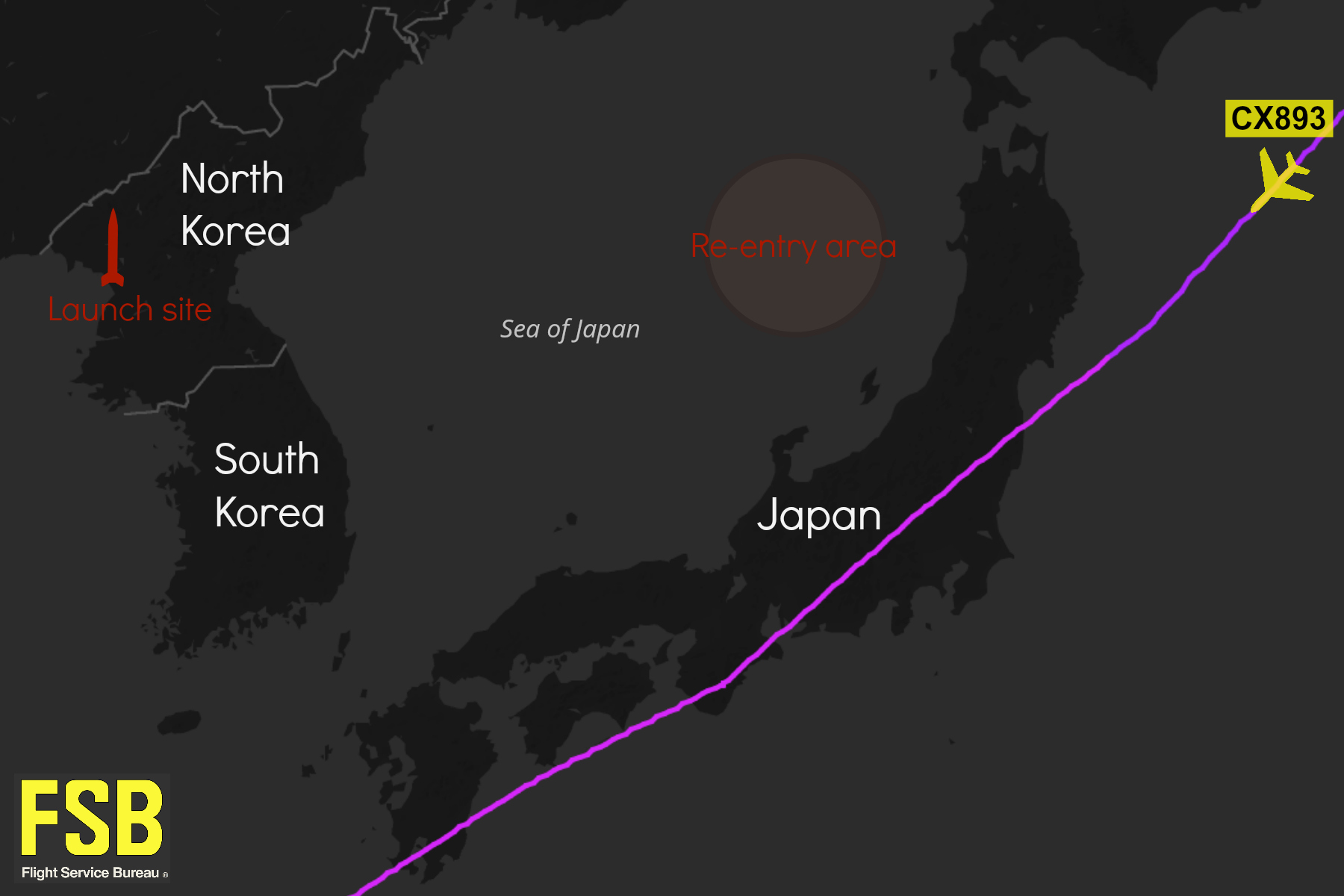

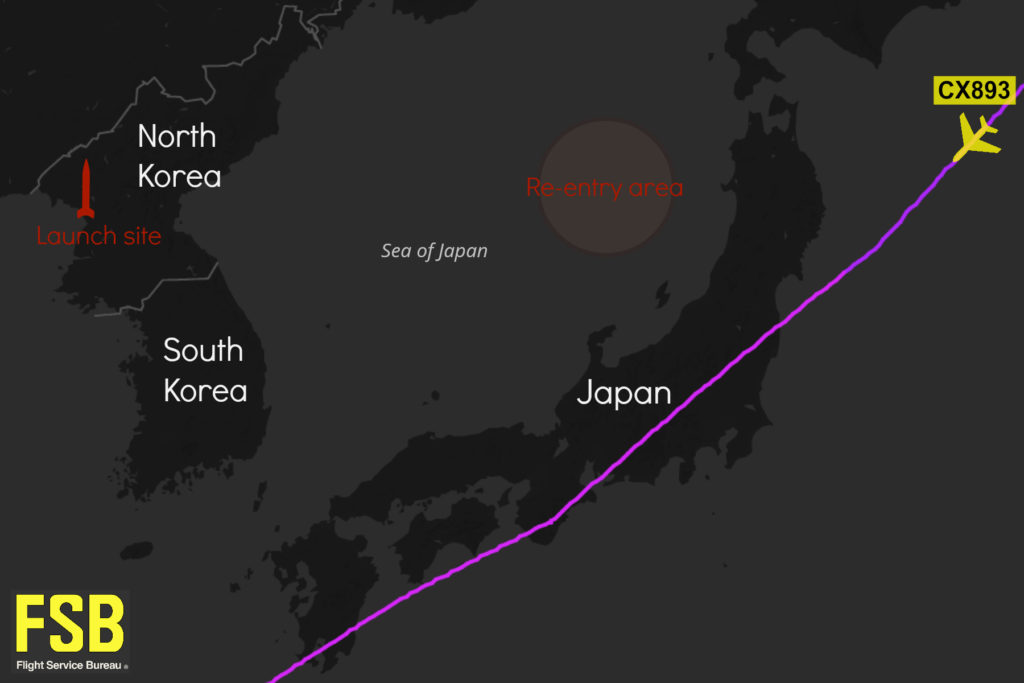

The chances of a missile, or part of it, striking the aircraft are not as low as they may initially appear – particularly given that all the missile re-entries in recent years are occurring in quite a focused area over the Sea of Japan. The risk to overflying traffic is arguably greater from ballistic missiles than cruise missiles, because these can break up on re-entry to the atmosphere (as happened with the 2017 tests) meaning that a debris field of missile fragments passes through the airspace, not just one complete missile.

Advice to operators

- Consider rerouting to remain over the Japanese landmass or east of it. It is unlikely that North Korea would risk or target a landing of any test launch onto actual Japanese land.

- Check routings carefully for arrivals/departures to Europe from Japan, especially if planning airways which connect with the UHHH/Khabarovsk FIR at waypoints IGROD and AVGOK.

- Read OPSGROUP’s Note To Members #30: Japan Missile Risk published in Aug 2017.

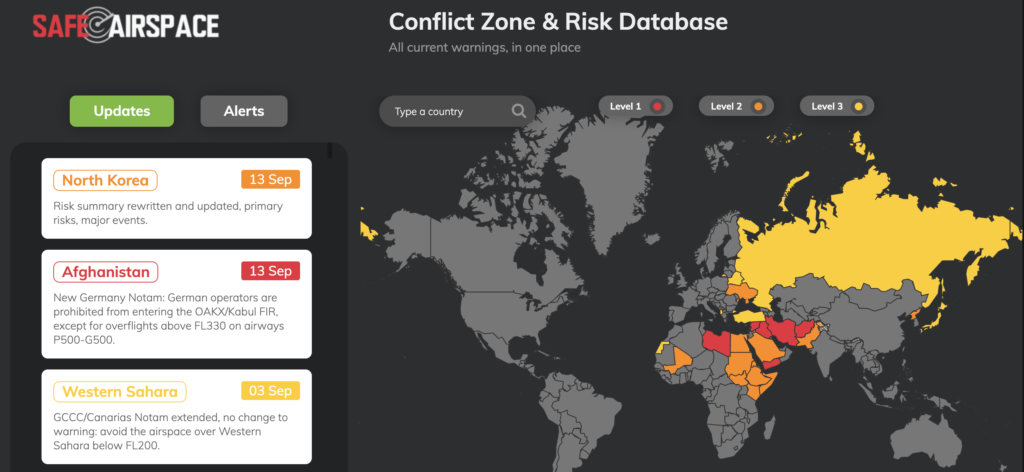

- Monitor safeairspace.net for latest updates to airspace warnings issued for North Korea.