The big talking point of the moment – Airbus and Cathay Pacific’s project to have only one pilot in the cockpit during cruise.

So let’s take a look at what this might mean for safety, operations and pilots worldwide.

The headlines are misleading

Cathay and Airbus have not designed a new A350 which no longer needs pilots operating it. There is no mega computer AI robot involved which is stealing our job.

The plan is to simply allow one pilot to go and rest during “quiet cruise” phases, while another pilot remains in the cockpit vigilantly monitoring (and probably with toothpicks propping their eyes open). This will allow them to potentially reduce the number of crew required on long haul flights, and while it means a change to procedures it is not really, as many are reporting, a leap towards pilotless flight decks.

Maybe just a small step

So, what are the considerations here that people are talking about?

Cathay Pacific are in talks with Airbus on this project

GermanWings

The GermanWings accident resulted in a rule that there must be two persons in the cockpit at anytime. So if a pilot needed a bathroom break, a cabin crew member was required to come in. This was fairly contentious at the time because, as many pointed out, what is a cabin crew member going to do if a “situation” arises?

This rule was eventually revoked, in part because EASA and other authorities brought in new regulations relating to pilot psychometric testing. However, with only one pilot in the flight deck, this does raise various safety concerns – from events similar to the GermanWings accident, to the question of pilot incapacitation or even, what do they do if they need the loo?

What about the AF447 accident?

AF447 was, in part, attributed to the experience levels of the two crew in the flight deck – both First Officers while the Captain was out sleeping.

Using cruise relief pilots is not a new thing though, and in order to operate with a single pilot, that pilot will presumably need to meet a minimum experience level. Additionally, the Captain will maintain the decision as to when they leave the flight deck in their First Officer’s hands.

Big storms on the horizon? Maybe stay in for a bit longer.

The lonesome pilot can also recall their colleague to the flight deck should a situation require it. So the question really comes down to whether a situation is likely to arise where, by having only a single pilot the result is more critical or catastrophic than if two had been present and therein lies the problem – because years of aviation safety studies have shown time again that there is a reason we operate with two crew.

Safety in numbers

Modern aircraft, and the A350 in particular, have many levels of safety and redundancy to support the crew. They can automatically fly TCAS maneuvers. They can carry out an emergency descent at the push of a button. In addition, Airbus are working to demonstrate that their aircraft and systems are robust enough to basically not really fail. They are also designing them to be able to autonomously handle any situation without pilot input for 15 minutes.

This will be a big deal. It will mean, should something fail, and the single pilot be incapacitated, that there is time for the second pilot to wake up and make it to the flight deck to solve the situation. However, recent aviation accidents involving malfunctioning systems (designed to minimize pilot workload), and ongoing concerns about automation complacency highlight the potential downside of such advancements.

Can ETOPS can teach us something?

The A350 was certified for 370 minutes ETOPS. That’s a long time. It is over 6 hours. 6 hours on one engine potentially. So what leads to this?

ETOPS is given to the operator, not the aircraft, and it is based on the operator’s ability to demonstrate necessary airworthiness, maintenance and ops requirements. It is really a statistical thing. If an operator hasn’t had an engine issue in a really long time then they are probably going to be able to get a better ETOPS approval.

So what does this have to do with only one pilot in the flight deck?

Well, it boils down to the same thing – statistics and procedures:

- How often does something go wrong in the cruise (which requires two pilots to handle it)?

- What procedures will be in place for ensuring safety and redundancy levels are maintained?

The answer to Question 1 might be “hardly ever”, but aviation safety improvements are built on the fairly simply idea that if there is a risk, find a way to mitigate it.

Even if that risk is minute, if it can be removed it should be. This is why astronauts have their appendix out before heading into space. This is why we have redundant systems onboard, or each pilot eats a different meal. Statistics might suggest an event occurring which a single pilot cannot deal with and which then results in a fatal accident or hull loss is tinier than a hair on a fleas back…

But if a risk exists that can be mitigates simply by retaining two pilots in the cockpit, then two pilots should remain.

A Disco onboard

They gave the A380 a bar and showers, now the plan is to have Discos…

DISCO actually stands for Disruptive Cockpit (I am not sure that sounds any better). This is the Airbus project looking at enhanced cockpit design to enable single-pilot operations on new aircraft.

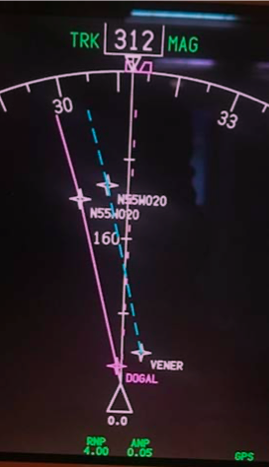

The DISCO concept is looking to place core technologies into the flight deck in a ‘multi modal’ way. Things like pilot monitoring systems which track eye movement, voice recognition for commands, improved ground collision avoidance systems, new navigation sensors.

And of course pilot health monitoring systems.

An integral safety aspect of this concept lies in the monitoring of the sole pilot, and the availability of a system to detect if they become incapacitated, and to alert the remaining crew member.

Not an entirely new concept

It is only happening in 2025

The plan is to implement this in 2025. That is 3 and a bit years of procedure writing, regulation making, testing and trialling before it is put into action, and there are a fair few obstacles that stand between now and that day :

- Regulators will be looking at their procedures with a fine tooth comb

- The pilot will probably need monitoring, particularly to ensure incapacitation does not occur (or if it does, the other pilot can quick-foot it back)

- There will need to be pilot training in place

- Airbus need to hit that 15 minutes of safe autonomy.

- And these systems will also need to deal with situations where ‘Black and White’ failures do not occur. When you consider the multiple, varied and often “illogical” failures which can arise from a lightning strike, a bomb onboard, or multiple computer failures this does not look as simple as Airbus might say

- The approvals for this do not just sit with the Hong Kong authorities. Any state that the airline might overfly with only one pilot in the driving seat is going to have to be convinced as well

- Passengers will need convincing…

And they still need to answer the question of the toilet. We all want a little more information on how that ‘specially designed unisex toilet’ to be used ‘in coordination with ATC’ will work.

A new flight deck concept?

If this happens, they won’t need pilots anymore

This is a contentious one to raise right now. Say ‘single pilot’ or ‘autonomous systems’ and a lot of pilots break out in a sweat, seeing themselves replaced by AI computers. But aviation has always been very innovative and those in it have always had to adapt to new technologies. Take a glance back to the 1980s and flight engineers were still a relatively common site in flight.

Ignoring the rather decimating impact of Covid though, aviation was growing, and it was growing fast.

Chances are it will again.

There are around 200,000 active pilots and forecasts suggested upwards of 500,000 would have to be trained over the next two decades to meet forecast growth demands. Even if every (long haul) flight deck sees the number of crew in it halved, it is still probably safe to say none of the current or new generation of pilots will be out of work anytime soon.

But we still are not convinced

There are unresolved questions here. The main one being “Why?”

You see, there is already this rather marvelous thing in an airplane – it can watch the pilot, it can monitor aircraft systems, and it can take over no matter what the failure or the complexity of that failure might be…

It is called “the other pilot”.

There is a good reason why aircraft are multi-crew machines. So why are Airbus and Cathay Pacific investing millions into developing systems which can do this?

It isn’t for safety…

This is being driven, not by manufacturers looking to increase safety, but by an operator looking to reduce costs. And for many, that appears an unwise and arguably unethical reason. Even if the statistical impact on safety is a 0.0001% decrease, that is still an unacceptable decrease when it is made for business reasons. There are also a great many places within an airline or operation where costs can be cut, and when cuts are made these should never occur at the price of safety, even if that price does seem negligible.