There are several reports that amidst the events surrounding the forced diversion of Ryanair Flight 4978 to Belarus last month, at least one MiG-29 was scrambled to intercept and escort the 737 to Minsk airport.

While military interceptions of civilian airliners are very rare, they can happen and for serious reasons. Which poses an important question – if a jet were to appear off your wing tip tomorrow, would you know what to do?

Each interception is potentially hazardous which is why ICAO publish rules and procedures (Annex 2) that both military and civilian aircraft should be following to minimise the risk. Each state is responsible for its own airspace, but where possible they should be following ICAO’s guidelines. For crew this includes knowing the actions to be taken and the visual signals to be used.

Here’s a break-down of what you need to know.

Why do they happen?

ICAO are very specific – an interception should be avoided and only used as a last resort. ATC must try and establish communications with you first. The primary reason is that they haven’t been able to talk to you.

There are lots of simple reasons why this can happen – usually a wrong frequency or perhaps they’ve forgotten to hand you over. In this instance they will try and contact you on 121.5 (which is one reason we monitor Guard), or via another aircraft. If that fails, ATC have a problem. You’re flying through their airspace and you’re not talking. It is not clear what is happening on board.

Incapacitation is a biggie, the crew may have fallen asleep or perhaps something more serious has happened as Helios 522 tragically reminds us. Or the aircraft may have been hijacked. Either way, they need to get someone up there to check things out.

What will they want us to do?

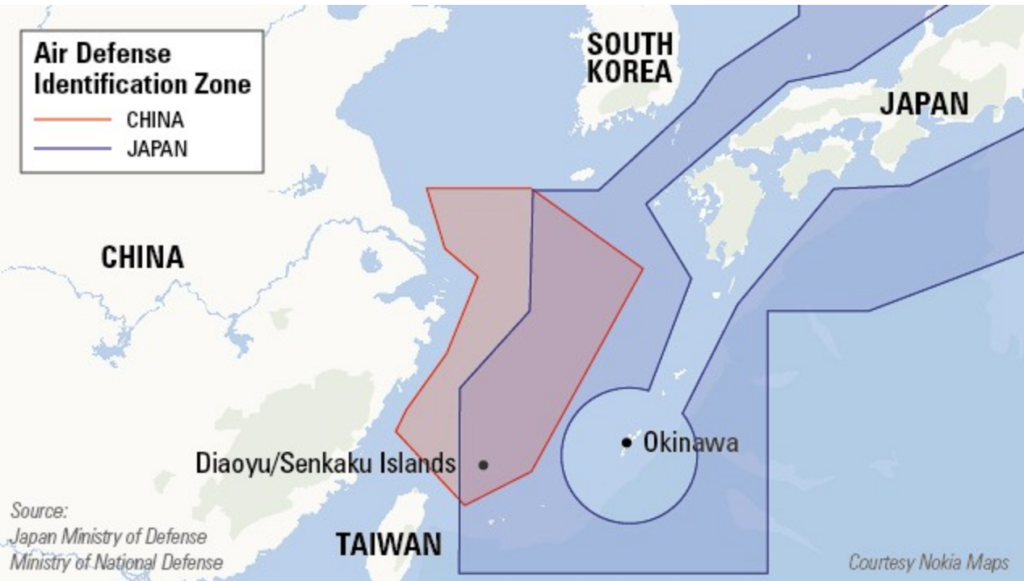

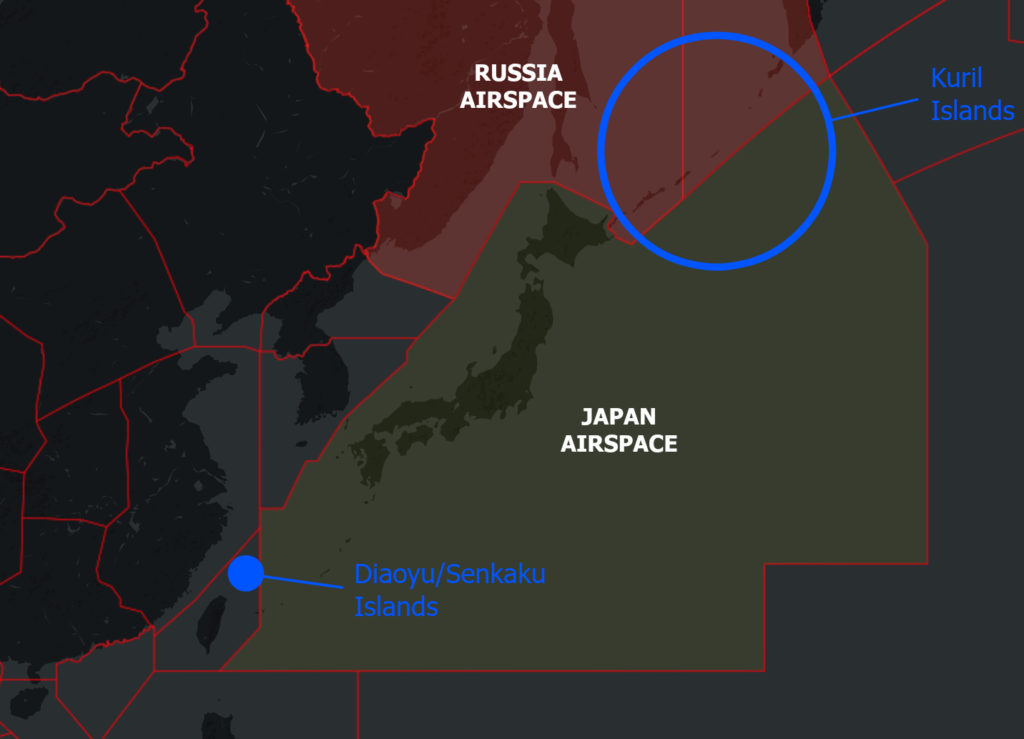

One of three things, depending on what the problem is. They’ll either want to identify you, communicate with you or re-direct you. The latter may be because you have strayed off-course or busted some kind of restricted airspace. Far less often it is because authorities may believe you are involved with illegal activity (such as drug smuggling) or or you are for some reason hazardous to other aircraft.

The Interception Manoeuvre.

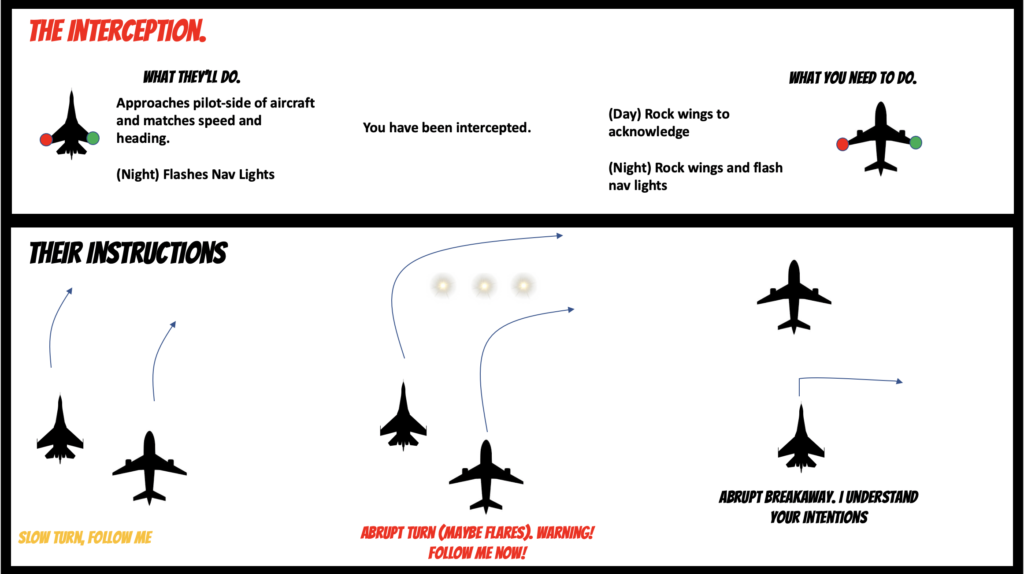

ICAO have a standard procedure for military aircraft to follow to minimise startle factor for you and decrease collision risk. A standard interception will take place in three phases, here’s how it works.

Phase I.

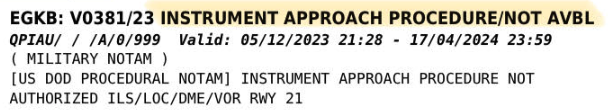

Intercepting aircraft should approach you from astern (behind). They will disable pressure reporting on their transponders – not to hide from you, but to avoid triggering a nuisance RA. They should still be visible on your TCAS but only as a TA. The lead aircraft will take up a position on the left, ahead and slightly above at a distance so as not to cause startle and to be clearly visible to the captain. It is likely there will be an accompanying aircraft which will remain behind you throughout. They will be trying to contact you on guard frequency (121.5) using the callsign ‘INTERCEPTOR’ or ‘INTERCEPT CONTROL.’

Phase II.

The lead aircraft will close slowly with you but not closer than needed to establish communications. All other aircraft will remain well clear of you.

Phase III.

What happens next depends on the situation. If they have finished their interception (they have identified you, re-established your comms with ATC or understand your intentions) they will perform a break away procedure to clear you.

Or they may need to divert or re-route you. In which case they will remain in position and clearly visible at all times.

What you need to do in the flight deck.

Stay calm. You’ll likely be startled. Slow it down and remember the following:

- Notify ATC (if possible). Make sure you have 121.5 active, the volume turned up and that your headset or speaker is working. Try and establish contact with them. Listen out for the callsigns above.

- Select Mode A on your transponder and squawk 7700 (unless ATC tell you otherwise). If you have ADS-B or ADS-C onboard, select the appropriate emergency function.

- Communicate (more on that below).

How do we talk to them?

The primary way they will want to talk to you will be in plain English on 121.5.

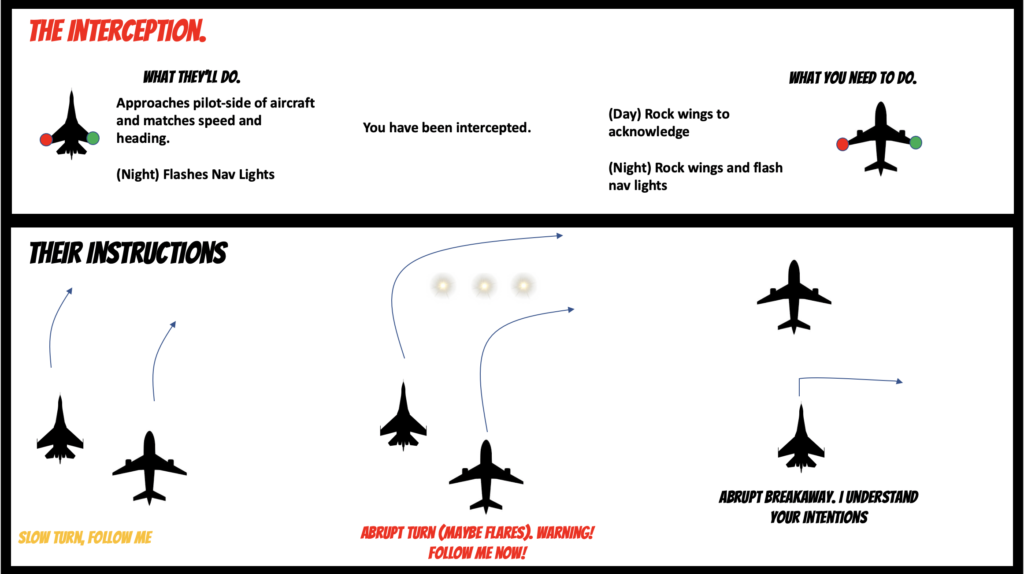

If they can’t raise you on that, they will use visual signals which is why they need to get so close to you.

There are ICAO standard signals used across most member states (including the US) that you need to know (or at least know how to find quickly). Here’s how they work:

When they want you to land.

If they can’t talk to you and want you back down on the ground they will direct you to an airport, turn on their landing lights, lower their gear and begin to circle.

If you intend to land you should lower your own gear and land. If the airport is inadequate, you should continue to circle 1000 – 2000ft, raise your gear and flash your landing lights until your escort re-directs you some place else.

What about if their instructions contradict someone else’s?

According to ICAO, if you receive contradictory instructions from other sources you should continue to comply with those from the intercepting aircraft.

Their duty of care.

You have to do as you’re told, but they should be looking after you. ICAO are very clear that nothing can be done during interceptions to unnecessarily put your aircraft or its passengers at undue risk. So, when they are requiring you to land, it is important to know they must take care to ensure your safety.

Firstly, they should not divert you to an airfield which is unsafe for your aircraft type. For civil aircraft this means the runway must be equivalent to at least 2,500m long at sea level, and have a bearing strength that is strong enough. The surrounding terrain must be suitable to allow for a safe approach and missed approach.

They must also take steps to ensure that you have sufficient fuel and if possible the airport they want you to land at is published in the relevant AIP.

Finally, they should give you sufficient time to prepare for the landing, including giving the crew a chance to check landing performance and brief.

Should I be worried about being shot at?

Seeing a fighter on your wing is an intimidating sight. But the use of weapons is very unlikely, especially if you are complying with instructions or are obviously unable to respond. ICAO have asked all contracting states for a commitment that all measures will be taken to refrain from the use of weapons (including to attract attention) as they endanger the lives and safety of everyone on board. However, that’s not to say they can’t be used. So the best defence is always to follow instructions.

Military interception of a civil aircraft is extremely rare.

While the diversion and alleged interception of Ryanair last month raises valid concerns throughout the aviation community it is important to remember that ICAO’s procedures have been designed to minimise risk across a broad range of scenarios. It’s important that we stay aware of them and how to apply them.