With Covid running rampant across the globe, other risky diseases have been forgotten somewhat, but there are a fair few out there which can pose a threat to crew on layovers.

So here’s a quick round up on the regions where you might need to cover up, dose up, or just be extra cautious during your international flight operations, split into sections based on the active travel health alerts that the CDC and other health authorities have out at the moment.

Red Warning Level 3: Avoid all non-essential travel

Guinea – Ebola

They had a serious outbreak earlier in 2021. Actually, cases have reduced significantly and the US has just removed their travel restriction which required travelers coming from Guinea to enter the US via 6 main airports only. Caution is still very much advised though if traveling in the country.

Venezuela – Infrastructure

Not a specific disease caution here, just a warning that their healthcare infrastructure is breaking down and if you are taken ill here you may not be able to access treatment. One to think about if you ever have crew on a layover here.

Amber Warning Level 2: Extra caution

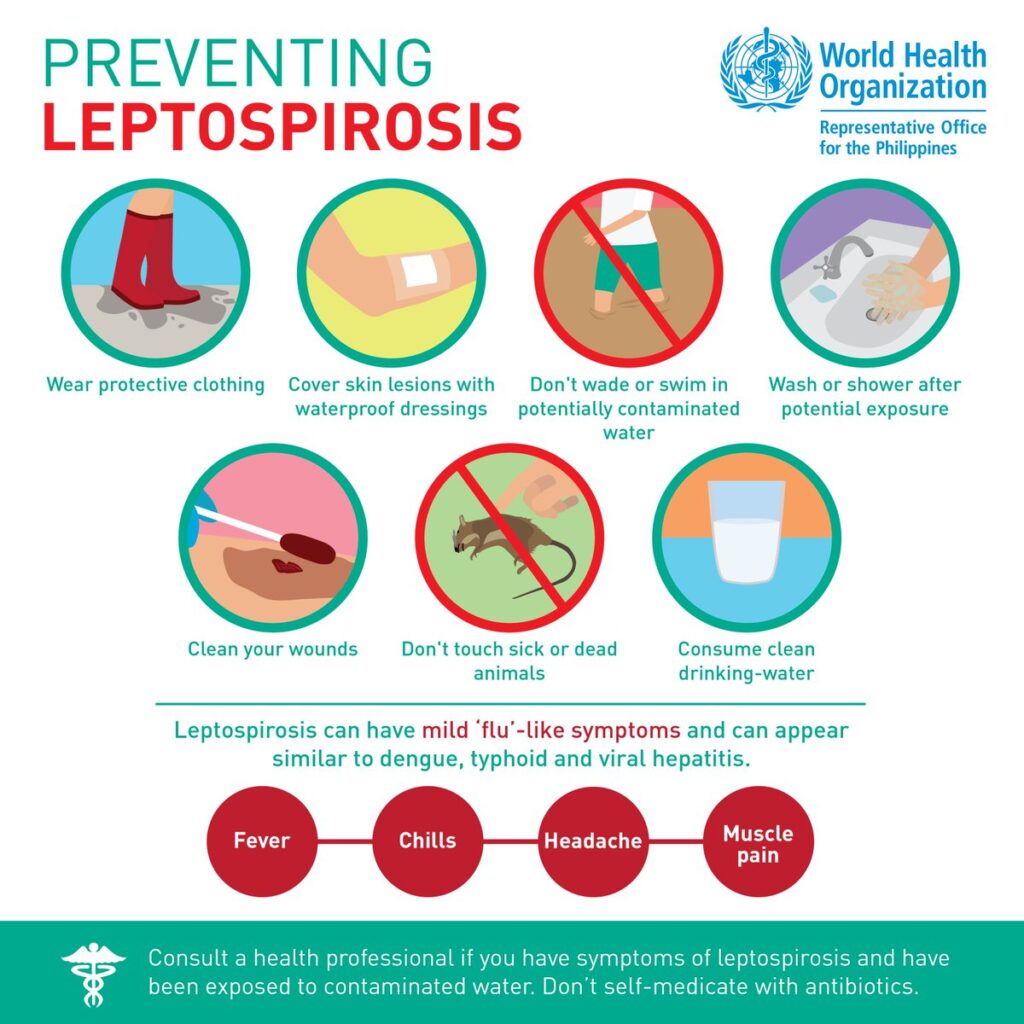

Fiji – Leptospirosis

This really prevalent in Fiji at the moment, particularly rural areas. It is caused by a bacteria spread around by animal pee, and can get into water and soil and live there for months. The main guidance is to avoid swimming or wading in water that could have had infected animals in it. Wear protective clothing and footwear and cover any cuts and scratches with waterproof bandages.

Because people often poke dead rats

Haiti – Rabies

Haiti currently has a big problem with rabid dogs. The bigger issue is that there is an extremely limited supply of treatment drugs in Haiti, so the recommendation is to get vaccinated before you head there.

Avoid dogs, and cats for that matter – even the cute baby ones. You can catch it if you are bitten, scratched or even licked, and treatment is only effective if administered early. Once symptoms present themselves it is often fatal. Plus, getting bitten by anything is never pleasant.

Polio – Africa and Asia

Everyone should be vaccinated against this. If you are not, get vaccinated (or don’t travel) because this is continues to be very prevalent in African countries and there is always a risk.

Nigeria – Yellow Fever

Consider getting vaccinated if you head here regularly, and try to prevent mosquito bites (also, because they carry loads of horrid stuff).

International flight crew generally are required to have had Yellow Fever Vaccinations – if you have not then take care because some countries will not allow crew (anyone) to enter who does not have a vaccination booklet if they have traveled to a Yellow Fever region recently.

What else to watch out for

Malaria

This fellow is to blame for a lot of the stuff out there

Malaria is a parasite carried around by mosquitos. There are actually four types of it, and it is in a lot of places!

The big risk here is it can take a while for symptoms to show. They reckon you’re most likely to have symptoms between 10 days and 4 weeks from being infected, but it could take as long as a year. The little beasties also like to loiter around in your liver, popping out at random times when you’re run down, and so can cause recurring illness for as long as 4 years after infection.

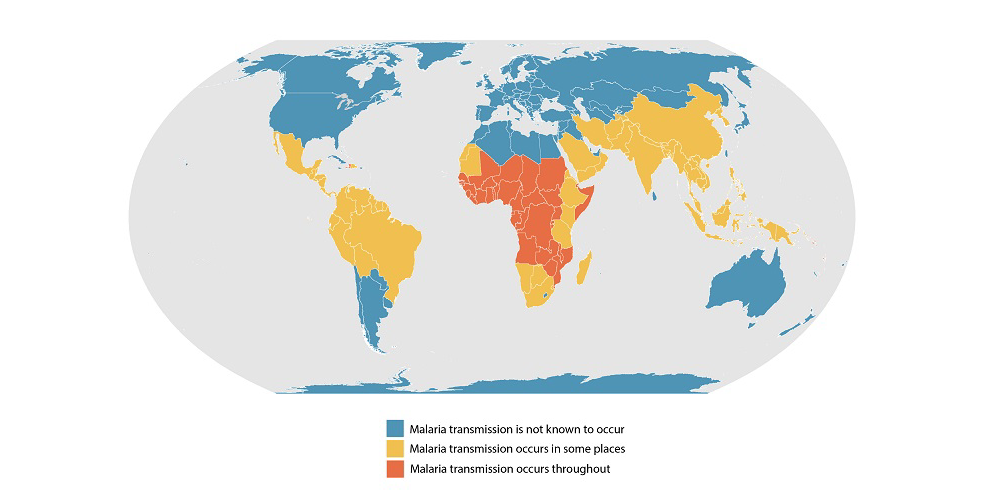

Where?

According to the CDC it is found in warmer regions, which doesn’t narrow it down an awful lot – basically anywhere hot and humid where there are places for mosquitoes to breed and grow. Just after rainy season is likely to be the worst, and rural areas will be more risky.

We have borrowed the CDC map because it is easier than trying to list everywhere to watch out.

Mozzies generally don’t like cold or high altitude spots

How to prevent it

If you are going to a Malaria riddled area then you can take preventative medicine, but watch out! Not many are approved for operating pilots because they can have some nasty side effects. Malarone is the most commonly approved (and generally has the least side effects) but we ain’t no doctor so check with an AME from your licensing state before taking.

The other option is to slather yourself in deet and wear long clothing to prevent the little nippers from getting at you in the first place.

The Symptoms

- Fever, sweats ad chills

- Muscle ache

- Nausea and sickness

So, basically generic symptoms of about a thousand other possible diseases.

If you have been to a malaria area and are thinking “I got chills, they’re multiplying”, don’t write them off as a random cold – tell a doctor so you can get tested because it can get very serious!

Dengue Fever

Another one to blame on the pesky mosquito, Dengue is common in over 100 countries, and over 400 million people catch it every year, 100 million getting sick and 22,000 dying. Dengue Fever is Malaria’s bigger, badder brother, and there is no specific treatment.

Like Malaria, there are also different strains of the virus meaning you can get different sorts, multiply times.

Where?

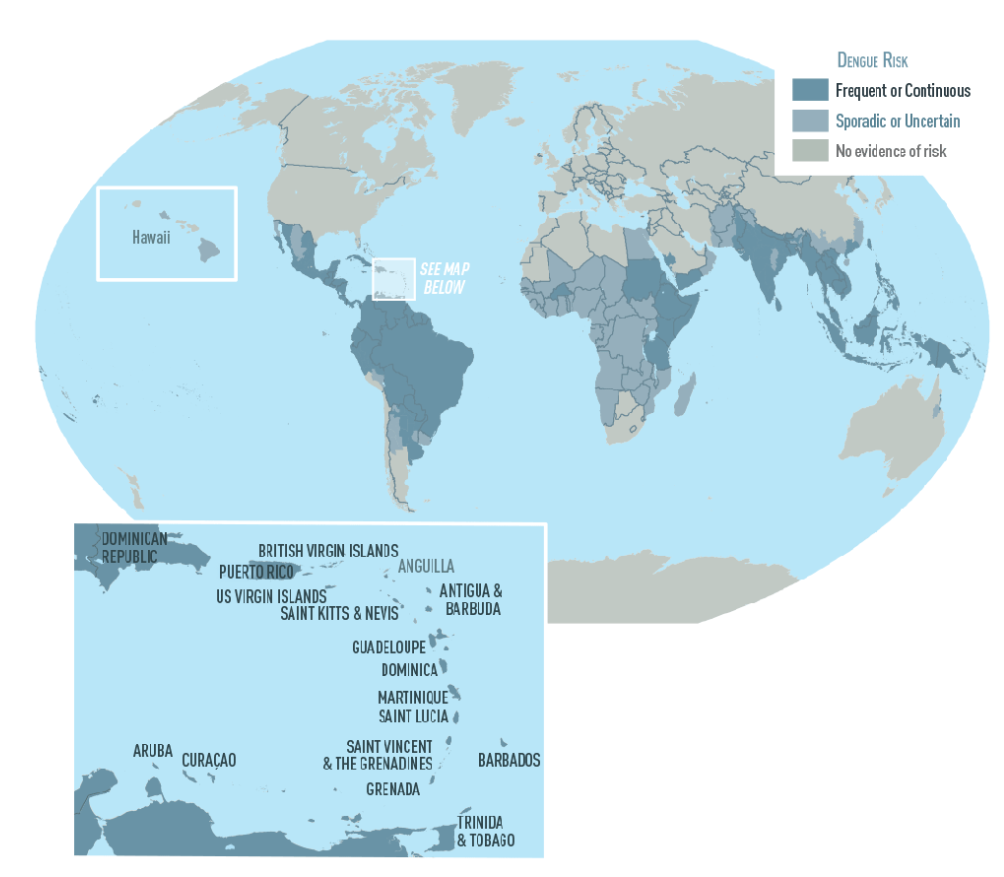

Outbreaks are coming across the Americas (including North America, although the mosquitoes aren’t there, people just head in already infected), Africa, the Middle East and Asia, and the Pacific Islands. It is most prevalent in tropical and sub-tropical areas.

There is currently a growing outbreak in Reunion.

Brazil has the highest rate of Dengue fever in the world.

How to prevent it

Best plan, don’t get bitten. Insect repellent is smelly, sticky stuff but it works. Here’s what the CDC recommends:

- DEET

- Picaridin (known as KBR 3023 and icaridin outside the US)

- IR3535

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Para-menthane-diol (PMD)

- 2-undecanone

There is a vaccine but it is only given to people who have been infected before and have a risk of getting severe Dengue, and for kids between 9-16 who live in a Dengue area.

The Symptoms

The early, mild ones tend to get confused with other diseases so again, ff you’ve been somewhere with Dengue, don’t assume it is something else. Go get tested.

Initial symptoms usually appear within 4 to 10 days:

- Nausea and sickness

- Rash

- Aches and pains, especially behind the eyes and in bone joints and muscles

These last around a week, unless you develop serious Dengue fever, which 1 in 20 do:

- Belly pain

- Vomiting (a lot)

- Bleeding from nose and gums

- Lethargy

Another handy map courtesy of the CDC

Zika

This one made the news a few years ago as it can cause serious birth defects. The symptoms for most tend to be fairly mild though.

It is also transmitted by our old friend the mosquito and there is no particular treatment so your preventative tricks are the best – don’t get bitten!

Chikengunya

Transmitted by mosquitoes, this has very similar symptoms to Dengue Fever and Malaria, and is found in all the same spots.

There is no treatment for it and no vaccine to prevent it, so preventing bites is really important.

There are currently serious outbreaks in Brazil, and in Asia (Vietnam, Philippines)

Ebola

This is a nasty one, often deadly, and causes lasting damage. They don’t really know where it comes from but it possibly started with monkeys and apes and was passed onto us human folk.

It is spread through direct contact with all the gory stuff that comes out of sick people.

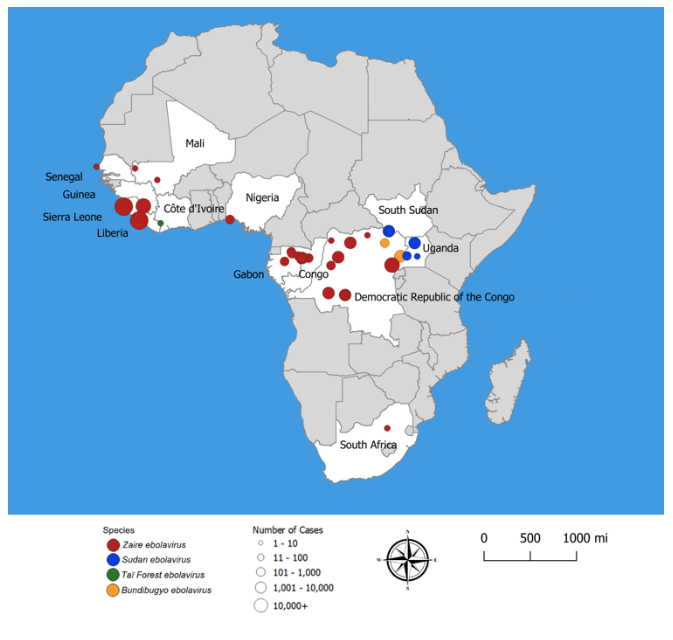

Where?

Guinea had a major outbreak in 2021, but cases have fallen again. The US previously restricted travelers from here, and from the DRC, only allowing entry through 6 specific airports.

In 2020, the DRC (formerly Zaire) had a major outbreak.

It is most common in African countries, particularly the central African countries, and along the north west coast.

Different Ebola virus strain outbreaks

How to prevent it

It is spread through bodily fluids so avoiding contact with these is important. You also should avoid contact with animals that live in Ebola regions. Bats, primates, forest antelope all carry stains of the virus. So don’t eat them.

There is a vaccine but it is only used in areas where an outbreak is occurring. There is medicine for treating it, and the do help survival rates. You also need medication to support blood pressure, to manage the fever etc, so this really is a serious disease which you do not want to catch

The symptoms

These can appear between 2 and 21 days of infection, usually around the 8 day mark. The main symptoms are:

- Fever

- Severe aches and pains

- Sore throat

- Loss of appetite

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Unexplained hemorrhaging, bleeding and bruising

Yellow Fever

This is pretty rare nowadays, but still on to watch out for across Africa and South America. It gets its name from the fact it generally causes jaundice.

Insect repellant works well. It is transmitted by the mosquito (again)

There is also a vaccine. It has been used for 80 years and it pretty well tested, safe and effective, with 1 dose providing life long protection. In fact, many countries require travelers to have had the vaccine if they are entering from a country (or have visited one) where there are high incidences of Yellow Fever.

Meningitis

This is serious – it makes your brain and spinal cord membranes swell up which sounds horrid and painful. It can be bacterial, viral, parisitic, fungal, amebic… so there are a bunch of different sorts all with varying degrees of nastiness.

Good news though, there is treatment for most, and vaccines. You have likely had some already, it is another one that flight crew are often vaccinated for because this can be caught from all over the place. Bacterial in particular can be in food.

General travel recommendations

The CDC has good guidance for flight crew which you can read here.

Many international airlines require their crew to have the following vaccinations, and they are often recommended in general for any traveller:

Cholera – Africa, Asia, Central America and the Caribbean

Diphtheria – Africa, south Asia, former Soviet Union. This protects you against Diptheria, polio and tetanus

Hepatitis A – Africa, Asia, Middle East, Central and South America. This is common in places with poor sanitation and hygiene and can be picked up a lot of ways.

Hepatitis B – Africa, Asia, Middle East, Central and South America. This is spread by bodily contact generally.

Japanese Encephalitus – Common in rural areas of Asia with a tropical climate, after the rain season. It is also found in western Pacific island and near Pakistan, China and Australia. Actually, it is rarely found in Japan because they did a mass immunization program years ago. There is a tick borne version too. Also with a vaccine available.

Typhoid – the Indian sub continent, south and south east Asia, South and Central America, Middle East