Here’s a look at some of the hottest and highest airports out there, and the challenges you might want to think about if operating into them.

Airplanes like to play it cool

What is it about hot and high airports that our airplanes don’t like? The obvious one is the air density – engines like their air cold for better performance, and wings like air nice and thick for better lift.

What can you do to keep them happy?

- Think about how you start the engines – If it is hot out, the air is thin, and you start throwing things like tailwinds into the mix, then it is going to be a recipe for some grumpy engines

- Consider towing – move to a different start point for better air flow

- Check that ground power unit – You might want to ask the engineer to see if two might be better (they can over heat too!)

- Check that take-off performance – and check it early. If it is limited you’re going to have to throw some passengers or cargo off, or put less fuel on to keep the weight down

- Watch you altitude constraints – If you are particularly heavy your climb performance is going to suck and where the airport is high, there is often other high stuff to think about too

- Once you’re in the air – if you are struggling to meet restrictions then keep the speed back, make sure you’re using all the thrust available to you and if that still don’t work – let ATC know!

People like to play it cool

People get grumpy when they are stuck in a jam-packed, sweaty tube. And I am not just talking about your passengers. Think about the poor F/O too.

If you’ve sent them out into the sweltering heat to do the walk around then it might be kind to have an APU running and some cool air blowing for their return. It will help with the rest of the flight too – you probably don’t want to be sat next to someone who is sweaty up a stinky storm for the next however many hours.

Jokes aside, it can be a safety thing too. A performance study by NASA showed operators in temperatures of 80°F (27°C) made approximately 5 errors an hour, 29 errors over 3 hours. At 90°F (32°C) this increased to 60 in 1 hour and 138 in 3 hours. So 1 mistake a minute. If you consider how many critical tasks a pilot carries out in that hour on the ground prior to departure that’s concerning.

When your environment heats up above 95°F usual cooling methods like radiation and convection stop working. Your body’s only option is to pump blood to the skin to release heat and get you to perspire. Up to 48% of your blood is pumped to the surface level, which means useful things like your brain which are less close to the surface are getting nearly 50% less than normal.

There are a few sorts of “hot” pilot we don’t ever want to see

Brakes break

High OATs means hotter brakes, and longer cooling times. But it is the high elevation that really causes issues here because your groundspeed is going to be much greater for the same IAS. The result is much more work for your brakes which have to slow down that big hunk of metal.

If you are lucky enough to have brake fans then switch them on as soon as possible. If you don’t, then keep an eye on those temperatures, especially during the taxi out.

How long it will take your brakes to cool down is dependent on your type of brakes, type of aircraft, how hot it is outside, how hot the brakes actually got. Aircraft will have their own max temperature for takeoff limit which is important because retracting your gear with hot brakes is an increased fire hazard, and aborting the take-off with already hot brakes is an even bigger hazard.

A (very) general rule of thumb is something like 2 degrees every minute (at 15°C OAT) will give you a (very) rough estimate.

You’re not going far with hot brakes and burst tires

Energy Management

Make sure you have some coffee and a snack. Oh, sorry, the airplane energy. Also worth thinking about because it is going to be harder to slow down and cranking out the old speed brake will have less affect with thinner air because, well, something to do with drag.

This can all get really critical really fast on the approach. A higher groundspeed also means a higher rate of descent, again making slowing down tough. Plan that configuration and manage the energy early.

At very high elevation airports (especially if they have terrain around) you might be trying to reduce your speed above your flap limiting altitude so keep an eye on your minimum clean speed and your flap operating limits.

FLARE!!

A higher ROD, reduced lift, turbulence from thermals can all mess with your flare. We aren’t here to tell you how to fly, so will leave it at a “have a think about it before you get there” top tip. Especially if your FO is taking the sector and hasn’t landed in these conditions before.

One more tip…

Celsius to Fahrenheit Formula: (°C x 1.8) + 32 = °F

Fahrenheit to Celsius Formula: (°F – 32) / 1.8 = °C

Which airports are highest on the list?

Topping the list is ZUDC/Daocheng Yading Airport which sits at a whopping 14,472ft. ZUBD/Qamdo Bamda airport holds the number two spot at 14,216ft closely followed by ZUKD/Kangding airport at 14,042ft.

These airports are so high that the hot bit is less of a factor, but the altitude is a major one – 14,000ft is a limitation on some aircraft.

Airports at these altitudes will have special procedures for take-off and landing and you are unlikely to be operating into them without prior training. So, which should we pay attention to?

Daocheng Yading Airport

The Hot and the High

FAOR/Johannesburg airport sits at an elevation of 5558ft. Predominantly NW winds on the ground often lead to a tailwind for the approach to runway 03L/R which makes the energy management more challenging.The runways are 14,505ft and 11,171ft (so you have enough).

Johannesburg can heat up to the high twenties (80°F) in the summer.

HAAB/Addis Ababa Bole airport has an elevation of 7625ft and also some very high MSAs in the near vicinity. There are high altitude constraints for the departure due to close in terrain, and they need to be monitored (particularly if you are heavy and it is hot out). A challenging RNAV approach makes flight path and energy management more challenging.

The radar at Addis is fairly intermittent so you are going to have watch that terrain avoidance and energy management yourself.

MMMX/Mexico City This spot has an elevation of 7297ft, and MSAs of 19,400ft, 14,800ft and 12,100ft. The terrain surrounding the airport means some interesting arrivals and departures and the need for some accurate tracking. The tight arrival also means some low platform altitudes. The ILS for the 05 runways are slightly steeper (3.1°) adding to your energy management concerns. We’ve also heard that ATC sometimes keep you fast until 5000′, which can make slowing down last minute more tricky.

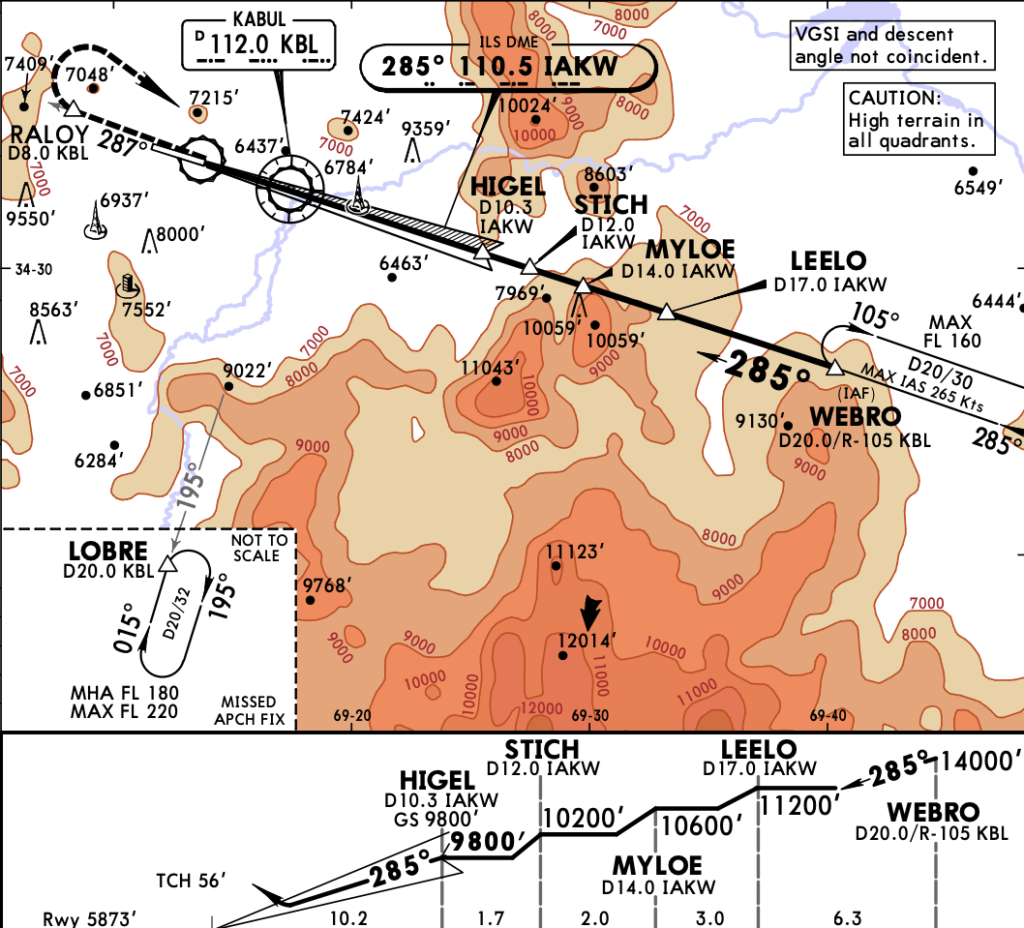

OAKB/Afghanistan I know what you’re thinking – there are probably bigger threats at this airport than the elevation, but despite the security risks here, it is a fairly frequented airport. Kabul tips the big three boxes – it has an elevation of 5877ft, an MSA of 17,500ft and it can get toasty warm in the summer months. The ILS for runway 29 starts from 14,000ft and the need to keep aircraft high due terrain can mean you suddenly find yourself diving down, while trying to slow down, with not many track miles to go.

You will probably want to keep you speed back on the departure to meet the minimum climb rate of 450ft per 1nm.

OAKB/Kabul approach starts from 14,000ft (Credit: Jeppesen)

The just plain high

SLLP/La Paz Ok, we will add this one because its a fairly major international airport. The Bolivian airport has a 13,124ft runway which lies at an elevation of 13,314ft making this an Overall Top Ten winner. The surrounding terrain (it sits in the Andes Mountains) means MSAs up in the flight levels – FL220, FL230 and a paltry 18,000ft.

Your TAS here is going to be around 25% higher than your IAS. The high elevation means it is generally cooler, but the density is still going to be low leading to lower performance.

The just plain hot

Basically anywhere in the Middle East in the middle of summer is going to tick this box.

OMDB/Dubai has been known to hit temperatures of 50°C. Hot means bumpy – you can expect some crazy thermals on the approach and an easy tendency to mess up the flare and float when that thermal catches you at 30 feet. Some airports (Dubai being one of them) temperature correct the ILS to account for the extra heat, so if you are doing height checks be aware of the discrepancy because of temperature.

OEJN/Jeddah is another spot known for getting very hot. It is also a very large airport with looooong taxis so keep a good eye on those brake temperatures for departure.

Where else?

Let us know any airports you think deserve to be on this list! Leave a comment or send us an email.

OPSGROUP members can check out AirportSpy – we have started to add Airport Lowdowns in here which cover the big threats (like hot and high!)