Fuel is to airplanes what coffee is to pilots – something you just cannot fly without. But just as there are different types of coffee, you’re going to come across different types of fuel as well…

The Menu

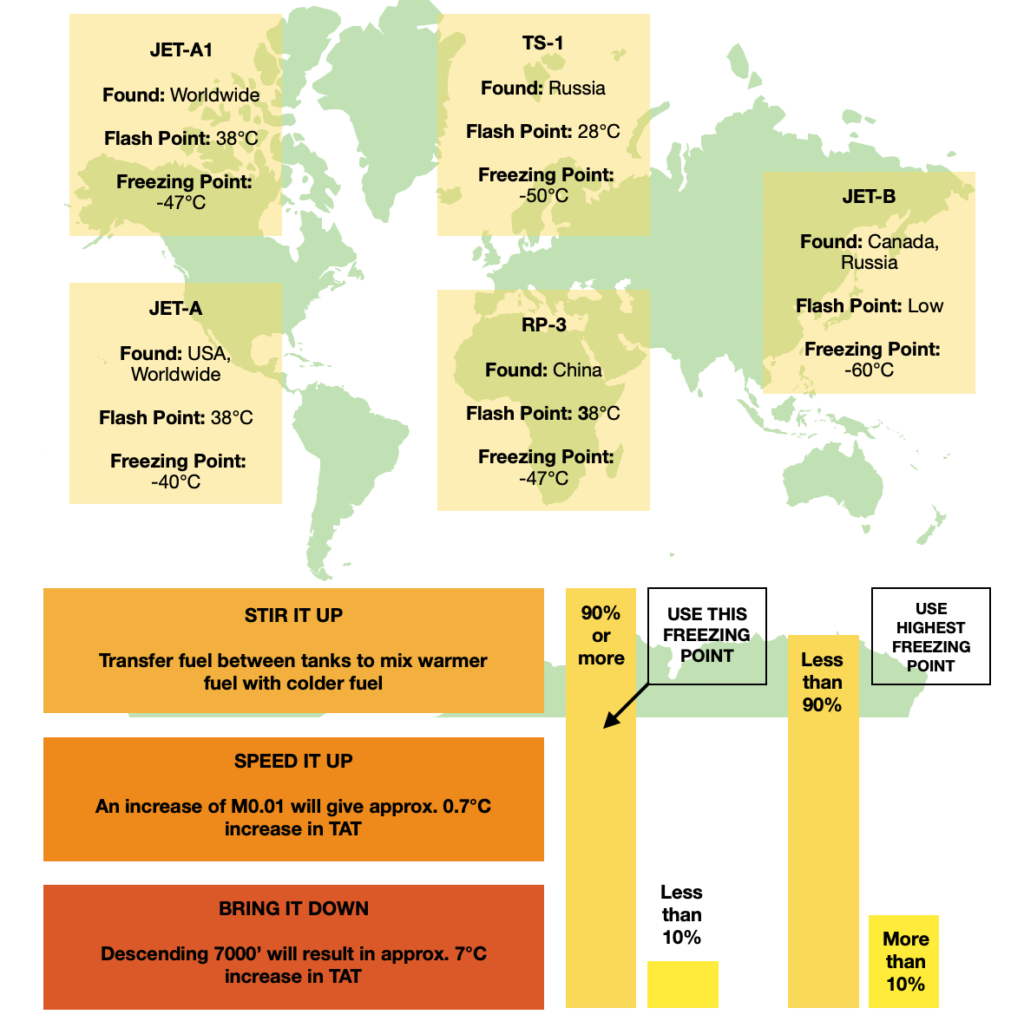

Jet-A1 – The most traditional drink, it is straw coloured with a flash point of 38°C (100°F), and a freezing point of -47°C.

Jet A – Another tasty kerosine grade fuel which will work just fine. The flash point is the same but this turns into an icy slushie at only -40°C.

Jet B – A delicacy from the Northern Regions. This is a cocktail of kerosine and naphtha – the stuff dragons produce out their nostrils (ok, that is not true, but it might as well be because this stuff is hard to handle with its higher flammability). Wide cut, and only really used in colder climates, with its freezing point of -50°C.

TS-1 – A Russian cocktail, more flashy than most at 28°C, but with a freezing point of -50 °C. It is also sometimes called RT (which looks like PT when it is written in Russian). RT is a superior grade TS-1, but not widely available.

RP – Brewed in China, the RPs come in a variety of styles. RP-1 has a freezing point of -60°C, RP-2 -50°C, but it is RP-3 we really recommend because it is basically Western Jet-A1 produced at export grade.

Chip fat oil – Not literally, but if you fly into a remote airport in some regions you might find fuel is not of the standard required. Look out for anything that isn’t straw coloured, doesn’t smell right, or has things floating in it.

Cutting it wide

Cutting it wide

Wide cut fuel is a mixture of kerosene and gasoline (Jet A1 in comparison is highly refined Kerosene). Wide cuts are not often recommended by airplane manufacturers because the quality and performance specifications are generally not as good.

If you are going to use it, there are likely going to be some pretty specific operational procedures involved because these fuels are much more volatile. Things like over-wing fuelling is generally a no-no, and the filtration system is going to appreciate a slow flow so it can keep up.

All those numbers

Fuel doesn’t freeze like water. It is not liquid one minute and ice the next. Instead it turns into a strange, slushy porridge consistency.

What’s more, if you have a mixture of freezing points, the freezing point won’t be a nice in the middle -44.5°C so the only reliable way to work this out when you’ve mixed a load together is to take a measurement – assuming you’re carrying your own Fuel Freezing Point Measuring Gadget…

If not, the next best method to use is this –

- 90% or more of your fuel is one type? Use that freezing point.

- 89% or less of your fuel is one type? Use the highest (worst case) freezing point.

- You have 900 gallons of Jet A1 freezing at -47°C and 100 gallons of Jet A freezing at -40°C? Then call it -47°C and be off on your merry way.

- You have 899 gallons of Jet A1, and 101 gallons of Jet A? Then take the highest freezing point which in this case would be Jet A at -40°C

Do we really care about freezing points of fuel?

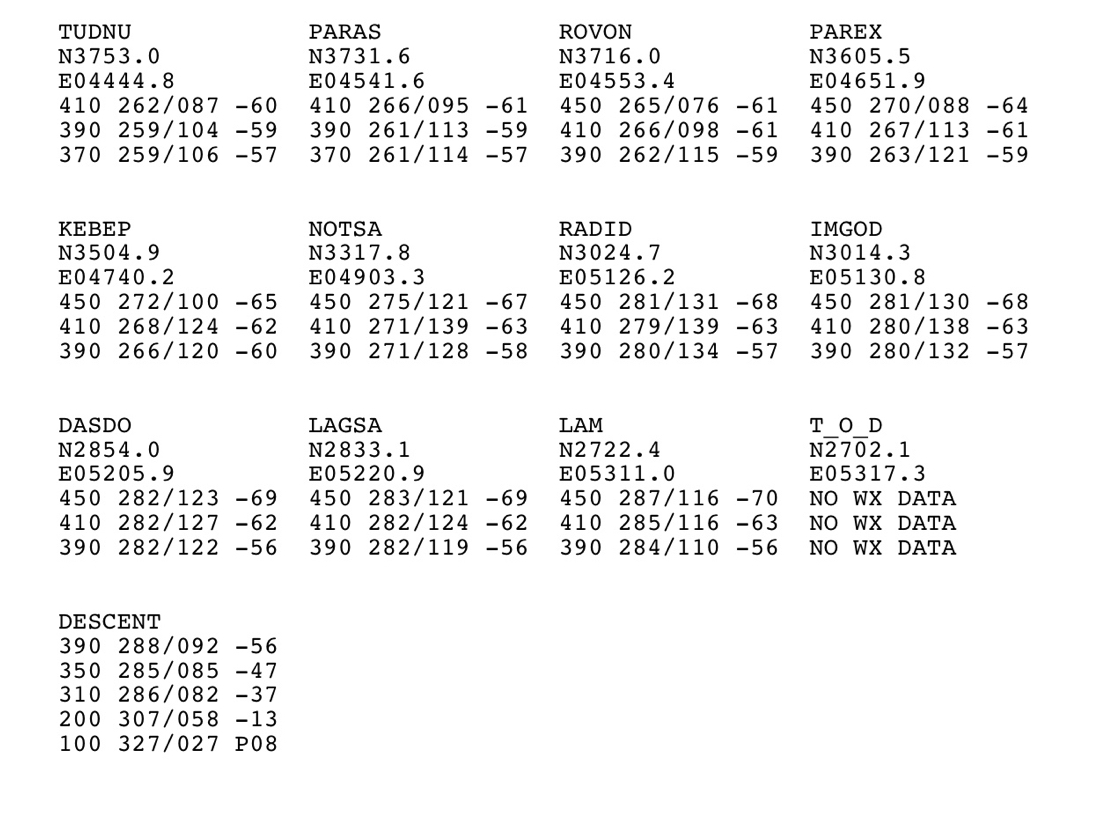

Yes, very much so, especially if you are flying some long haul treks over the North Pole at high altitude in the winter.

With outside air temperatures lower than -60 degrees, freezing fuel can get you into some very hot water, (or cold fuel to be more accurate.)

In Jan 2008, British Airways Flight 38 crashed just short of the runway at EGLL/Heathrow after flying from Beijing, China. They had been cruising between FL350 and FL400, with OATs reported to be between -65 to -74°C. While the fuel itself never froze, it did become cold enough for ice crystals to form in the fuel system.

These pesky little ice particles blocked stuff up and reduced the fuel flow, starving the engines, and causing a big loss in thrust right when the pilots needed it.

The temperature gets darn cold at altitude!

What can we do about it?

Ultimately, you need to turn up the temperature! There are only a few ways to heat your fuel up if it starts getting too chilly:

Stir it Up – Unlike Bond who preferred his drinks shaken and not stirred, mixing cold fuel with warmer fuel makes it better. Some larger aircraft with complex fuel systems do this automatically, but if you are able to do so manually there will probably be a checklist and following it to avoid turning off the wrong pumps might be wise.

Speed it Up – Flying faster means more drag which means more energy converted into hotness. Not much though… an increase in Mach 0.01 will increase the TAT by around 0.7°C, and increasing your speed also increases your fuel burn.

Bring it Down – Warmer air will help, and by descending 7000’ you can increase the TAT by around 7°C. In seriously cold air masses, descent to at least FL250 might be required, but this all means a much higher fuel burn.

Tanker? No thank ya…

Tankering fuel if you are operating into somewhere chilly might cause you some problems. The fuel is likely to get cold in flight, and up the likelihood of some frosty wings on the ground. So check the de-icing situation at your destination if you are tankering and it’s cold out.

Some other useful info

- 1 imperial gallon = 1.2 US gallons.

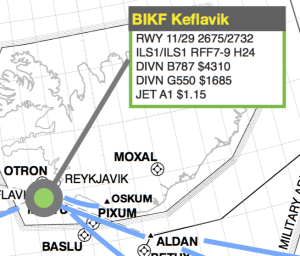

- You can monitor the price of jet fuel here.

Give it to me in plain English.

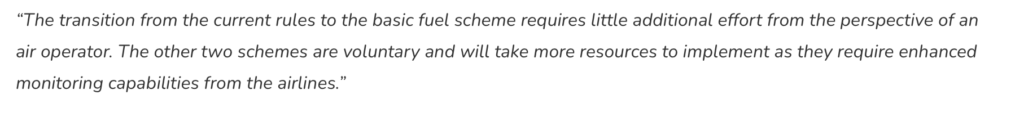

Give it to me in plain English. So let’s look at the schemes.

So let’s look at the schemes.