Ask a pilot what their worst fear is and one of the responses you will probably hear the most is FIRE! Ironically, an aircraft’s engines only actually work when they are “on fire” so not having a fire “onboard” could be problematic…

But a fire in the cabin or cargo hold is a rather different deal. So, here is a look at what many consider to be one of the most challenging and concerning problems they could encounter in-flight.

For those who don’t think it is that scary.

A CAA study back in 2002 looked at aircraft crashes due to fires onboard and discovered a rather fearsome statistic – the average time it took for an aircraft to become catastrophically uncontrollable was under 20 minutes. Various fire tests saw that a fire allowed to spread through the aircraft’s overhead area could become uncontrollable in just 8-10 minutes.

The average time for a crew to get their aircraft onto the ground was around the 17 minute mark.

So, not much time to spare.

The infamous Nimrod ditching (a favourite CRM example of decision making) shows how quickly a fire can disable an aircraft.

The problem is aircraft are built to burn.

Aircraft skin is thin and can burn fairly rapidly with high temperatures

Well, not literally, but there is a significant amount of flammable, combustible and generally burnable bits onboard. Add in the fact there are very hot bits (the engines) linked to big chambers full of fuel and the risk of an un-contained fire suddenly seems a lot worse.

Un-contained being the important word here.

Engines have fire identification and protection systems in them. So do cargo bays. So do cabins for that matter (Cabin Crew make wonderful fire detection and fire suppression systems). Aircraft interiors, and cabin fire fighting procedures, and the monitoring of Dangerous Goods transit have also developed significantly over the last decade or two.

So, the means to prevent or control fires before they become uncontrollable have increased.

Unfortunately, though, so have the number of devices coming onboard which could start a fire in the first place.

Lithium Ion batteries burn hot. They are hard to put out, and every passenger on your flight probably has at least one, probably nearer three of them (phone, second phone, computer, tablet, smart luggage, spare power banks, watches, electric toothbrushes…)

And of course phones are not the only potential fire hazard onboard. There are ovens (hot), hydraulic fluid (thankfully not in the cabin, but very flammable), electrical things (seats, tvs, lights), waste bins (in toilets for hiding illegally smoked cigarettes in), oxygen systems (a food delicacy for fires) and a multitude of wires.

Interior from the Swissair 111 accident in 1998 – caused by faulty wiring

An FAA study from 1995 to 2002 found reports of nearly 400 wiring failures. 84% of these were burned, loose, damaged, shorted, failed, chafed or broken. And this is probably not a representative number given how many might go unreported.

The Swissair accident was due to faulty wiring, with a secondary prominent factor being the flammability of materials that ignited and propagated the fire. The crash occurred just 16 minutes after the first alert message.

Let’s take a look at what can burn in the cabin.

Seat coverings, blankets, cushions, other furnishings, clothes… basically everything inside the cabin can burn.

In 1993 a Northwest Airlines B727 had a fire in the cabin and it turned out they were using 100% polyester blankets. Polyester actually melts more than burns, but it gets really hot when it does and tends to set alight to everything else around it. The incident led to the FAA developing new fire performance test methods and criterion for all blankets.

Interesting fact: Emirates actually make their economy blankets out of recycled plastic bottles. 28 of them per blanket.

Her hairspray is the most flammable thing, closely followed by the 1970s fabric

Actually, the burning ability of everything onboard is now monitored.

Since 1990, aircraft interiors have had to comply with a maximum total heat release of 65 kilowatt minutes per square meter, and specific optical smoke density of 200. Basically burn less, burn less hot, and put out less smoke if they do burn.

The current rules for what everything should be made of, and how burny/smoky/toxic they can be are contained in FAR/JAR/CS 25.853.

An FAA fire test with 5000 lithium ion cells

Crew training is important as well.

The training and ability of the crew to both fight the fire, and evacuate the aircraft is strictly monitored. The FAA require that an airplane can be evacuated in 90 seconds. For big commercial aircraft (these are Boeing stats) this means the slides have to be able to inflate within 10 seconds (15 if it is a big wing slide), and they need to be able to support 60 people sliding down at once.

It doesn’t take into account the huge heap of people at the bottom of the slide, but once they are out and away from the fire all bets are off.

90 seconds to evacuate 500+ people

But accidents still happen.

Between 1990 and 2010 there have been 18 major accidents involving in-flight fires which resulted in fatalities. During the 1990’s, the US saw, on average, one flight a day diverting due to smoke; and a report by IATA suggests there are more than 1,000 smoke related events annually.

That’s about 1 in 5,000 flights which is a pretty big number when you consider how many flight you will do in your career, or how many movements there are worldwide every day.

In 2010, a UPS B747 freighter crashed in Dubai following a main cargo deck fire which ultimately led to loss of control of the aircraft. The pilots were incapacitated earlier however due to the rapid build up of smoke in the flight deck.

What to do. The important bit.

1. Troubleshoot.

Finding the source should be a top priority. That means working out where the smoke is coming from.

If it is coming from something avionics related then you are going to want to switch it off. If it is something in the cabin then it might be locatable, reachable and extinguishable. Don’t forget to get your crew to check the lavs.

The terror…

2. Communicate.

One of the biggest challenges in dealing with a fire in the cabin is the communication between the cabin and the flight deck.

- Ensure there is a communicator in place who can pass messages to you and keep you updated.

- If you are trying to establish the severity of the situation, ask open, non-leading questions:

- “How much smoke?” could lead to “lots/loads/not as much as you’d see at a rock concert in the 60s…” . Instead, try “How many rows of seats can you see?”

- Establish whether they can see where the smoke is coming from, if they can get to the source, and if they can put it out:

- Ask about the colour, the smell, and while troubleshooting make sure you leave enough time for them to identify a change (after turning stuff off or on).

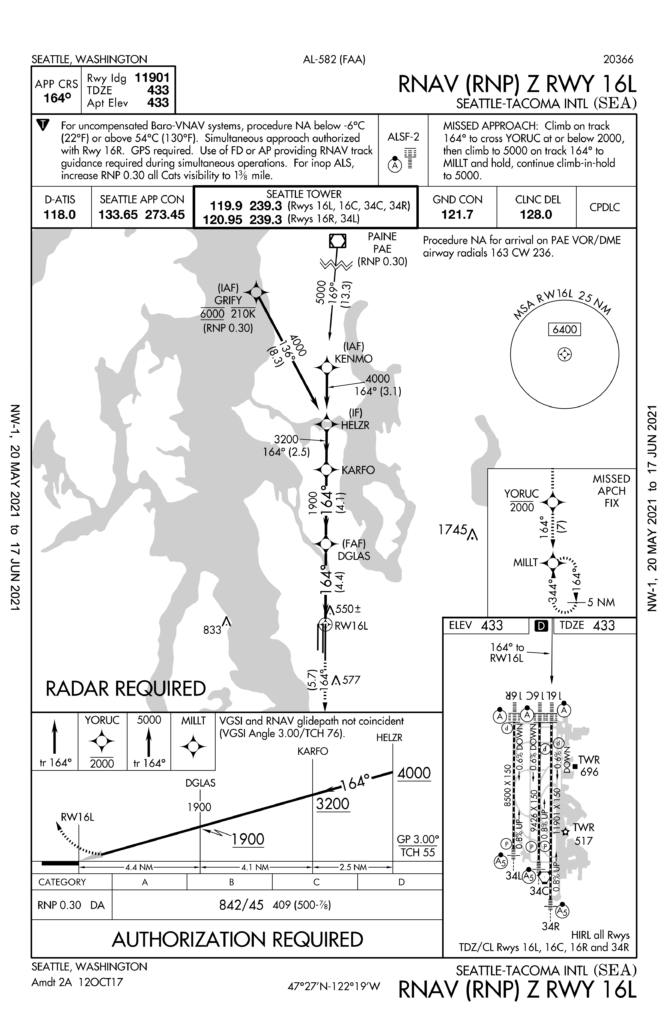

3. Keep flying!

Don’t forget to keep flying – one pilot should focus on the fire procedures (or on the comms with the cabin) while the other flies the aircraft! This probably means aiming for an airport.

Declare an emergency – this can be downgraded later if the situation improves, but get the support you need early on.

If there is an autoland option you might want to set up and plan for that in case the smoke in the flight deck builds up too much.

4. Don’t forget…

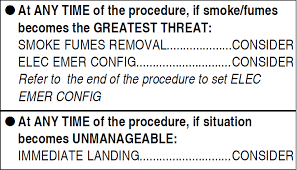

You have two procedures – one for sourcing and “fighting” the fire, and one for dealing with smoke (and fumes). If you need to, suck that smoke out!

On the ground.

Your Ops Manual will have a required RFF category for airports. However, this is based off the equipment available at an airport (and the response time). A Captain can chose to disregard this if the only option does not meet their RFF requirement.

The emergency isn’t over until you and the passengers are safely off. If the cabin is filling with smoke then a top priority is getting those engines switched off so your cabin crew can evacuate. If in doubt, evacuate!

Depending on where the fire is (and how the wind is blowing) you might need to avoid evacuating through certain doors. Getting folk away from the aircraft is critical. The main injuries resulting from the Emirates B777 accident in Dubai were some inhalation from passengers and crew, and heat stroke from the firefighters – it took 16 hours for them to bring the fire under control.

What to do earlier…

1. Have a plan

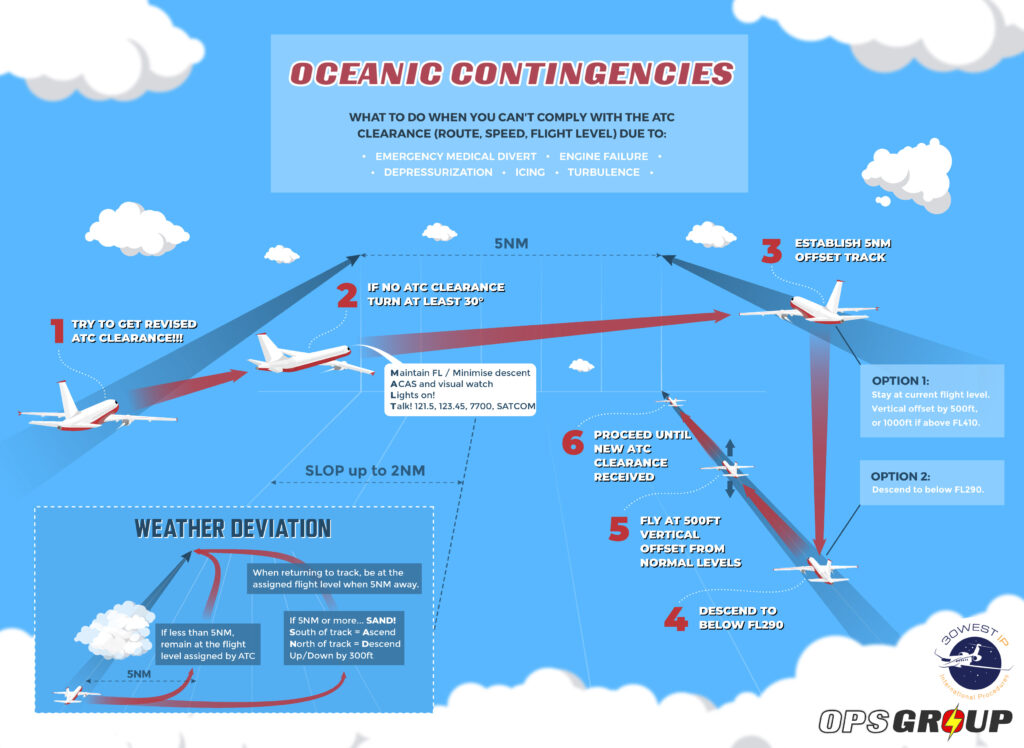

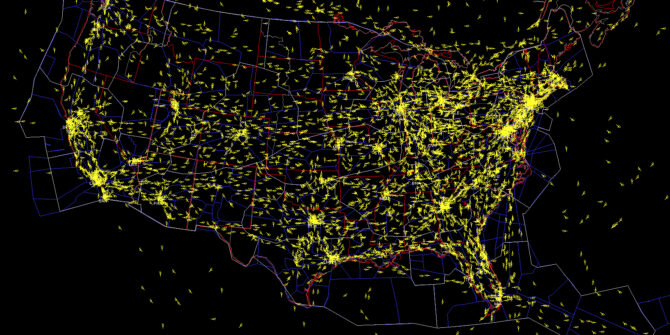

This means knowing what airports are around that you could go to if you suddenly, urgently need to.

- Check the weather and Notams en-route.

- Have something in the box ready (if it is a difficult airport to route to, or there is airspace to avoid, or if a straight in visual might not be an option).

2. Know what equipment you have onboard.

Know what it is, where it is, and how to use it:

- Halon: Great for electrical fires, not so good for you. If you are using this in the flight deck, get a smoke hood or oxygen on first.

- Remember PASS: Pull the pin, Aim at the base of the fire, Squeeze the handle or lever, Sweep it about from side to side like an aggressive elephant.

- EASA are recommending the removal and substitute of Halon Extinguishers because of their mean effect on the environment, and also on people.

- Oxygen masks: If there is smoke in the cabin, don’t drop these thinking it will help your passengers breathe better. Oxygen + Fire = not a good result, and their masks are not designed to keep smoke and fumes out anyway.

- Smoke hood: You look like a weird spaceman in it, and sound like Darth Vader, but this is a very important bit of equipment.

- If you are on the ground and evacuating, use this before doing the cabin checks.

- Fire Sock: For putting things in. Usually has some gloves nearby for picking the hot burning thing up with.

Fires can burn through aircraft skin, control surfaces and control cables and wires.

False Alarms

These do happen.

An IATA study saw 2,596 reports of fire/sparks/smoke or fume occurrences. Of these, 20% were false warnings, which meant 11% of the in-flight diversions were due to false warnings. 50% of cargo compartment fire warnings were also false.

Air spray is a common culprit for causing false alarms in toilets.

But – if you get a fire warning, treat it as real unless there is some very, very obvious something to suggest it is not.

FIRE!

They critical thing is to be prepared. Have that airport option in mind, know where to find the procedures (and familiarise yourself with them), and make sure that if it does happen, you and your team are ready.

A fire onboard is a time issue. Being prepared and ready will hopefully give you those extra minutes that could make a big difference.

Burning desire to read some more?

- The RAeS have two papers entitled ‘Smoke, Fire and Fumes in Transport Aircraft’. Part 1 is a reference paper with a lot of scary accidents discussed in it. Part 2 covers training recommendations. If you never read anything else on this subject, at least read these – most of the reports referenced in this article are pulled from these.

- Boeing’s Evolution of Airplane Interiors is quite an interesting read on the testing and cabin interior requirements.

- A briefing on Bad Air, Fumes and Contamination takes a look at other dangerous fumes that might be swilling about in your aircraft.