Putting ‘climate change’ in the title of a post on an aviation page probably isn’t the best way to draw in the readers. But this is not a lecture. Promise.

So, what is it about?

It isn’t about chemtrails. They aren’t a real thing.

It is about contrails. The wispy bits of whatever that your airplane engines fart out as you fly, or the ‘engine plumes’ if prefer to imagine your airplane resembling something like a peacock.

Contrails are basically water vapour. They form when the exhaust gases from the engine starts to cool and mix with the air around them. The humidity rises, the water cools and condensation occurs.

A small, small proportion of what is burped out of the engine is not water though, but impurities from inside the engine.

Things like sulphur particles. It only makes up about 0.05%, but these tiny particles give the water something to freeze onto and they cause tiny ice crystals to form.

The peacock. This might be photoshopped…

So why do we care about this?

They are quite a useful indicator of possible wake turbulence for us, but aside from that (and unless you are one of the pilots who likes to draw amusing pictures in the sky with them) then we don’t really care that much.

But maybe we should care a bit, because some contrails loiter up there for ages – these are known as homomutatus contrails. Frankly, anything which sounds a little like ‘mutant’ should cause concern, and these definitely do, because they are responsible for the word we shall not utter.

Ok, we will, just to be clear – global warming.

Not here to lecture though! Promise!

A little bit of science (still not a lecture)

So, the airplane burps out the water, it turns into contrails which then hang up there in the stratosphere. Aviation causes only about 5% of the water present in the stratosphere, so it isn’t a terrible culprit.

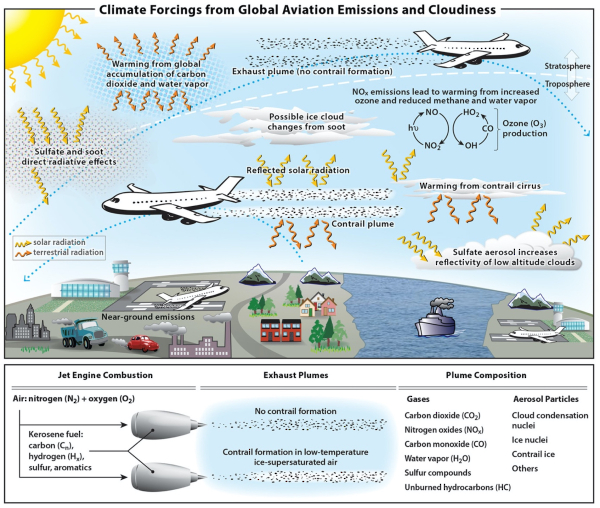

Unfortunately, though, those homomutatus contrails, plus the extra water, plus the ice particles – all that stuff left up there by airplanes – causes terrestrial radiation to backscatter. It also stores up some of the radiation coming in and the result is something they call ‘radiative forcing’.

Basically, extra heating-up happens.

So, airplanes are spitting out C02 and contrails, and the contrails are thought to be responsible for something between 20% to about 40% of all the radiative forcing aviation causes to occur (they don’t really know how much, but they reckon about that amount).

Just for info, not a lecture

So… why are we actually telling you if this isn’t a lecture?

We’re getting there, stay attentive!

Free Route Airspace (a big open area between 2 waypoints where you are routed in a straight-line between them) has already helped reduce fuel burn and C02 emissions. They reckon it saved about 40 tonnes of fuel a day, and reduced the C02 by about 150 tonnes a day.

So, the helping-the-environment plans are already helping you because it means less fuel burn.

ICAO and Eurocontrol, in conjunction with EDYY/Maastricht have now set up a project called the Contrail Prevention Trial.

The Contrail Prevention Trial will initially only take place in Maastricht and the plan is to sometimes re-route aircraft around atmospheric conditions that are most conducive to contrails.

The Contrail Prevention Trial

If you are routing through Maastricht airspace you might find you are given a re-route. It won’t be huge, it might mean a little bit of an increase in fuel burn, but it will hopefully mean a decrease in the contrails your aircraft produces.

You won’t really know, but some clever science person down on the ground hopefully will.

So, a little bit of science, no lecture, and some info on why, if you are routing through Maastricht sometime in 2021, you might be given a tactical diversion. Now you know why 😊

Here is the official announcement on it, found on the Eurocontrol homepage:

CONTRAIL PREVENTION TRIAL – MAASTRICHT UAC (EDYY) AIRSPACE

===========================================================

IN AN EFFORT TO MINIMISE THE IMPACT OF AVIATION ON THE

ENVIROMNENT, MUAC WILL BE RUNNING A CONTRAIL PREVENTION TRIAL FROM

18TH JANUARY 2021 UNTIL 31ST DECEMBER 2021 BETWEEN 1500-0500UTC

WINTER (1400-0400UTC SUMMER).

FLIGHTS MAY BE TACTICALLY REQUESTED TO DEVIATE FROM THE PLANNED/REQUESTED

FLIGHT LEVEL BY THE SECTOR CONTROLLER.

ANY FLIGHT FLYING VIA MAASTRICHT UAC SECTORS BETWEEN THESE TIMES

MAY BE CHOSEN. THE TRIAL WILL GO AHEAD DEPENDENT ON THE WEATHER

CONDITIONS.

MUAC AO HOTLINE +31 43 366 1428

NMOC ON BEHALF OF MAASTRICHT (EDYY) FMP

===========================================================