The risk of lithium-ion battery fires on aircraft is on the rise, with vapes, power banks, and laptops identified as the main culprits.

The FAA has reported a sharp rise in incidents, with some sources noting two thermal runaway events per week. EASA also raised concerns, issuing a new Safety Bulletin on May 27.

While rules are strict for Parts 121 and 135, private flights under Part 91 face fewer restrictions. Arguably, private jets are more at risk, and we’re doing less to protect ourselves.

- Business jets are smaller. A lithium-ion battery fire can quickly fill the cabin with thick, toxic smoke – up to 10 cubic meters from a single laptop battery in just two minutes. History has shown that smoke inhalation often causes the loss of an aircraft in a fire before the fire itself.

- Fewer crew members.With only one or two pilots and often no cabin crew, response capability is limited.

- The passengers we carry. Biz jet passengers often carry multiple personal electronic devices which increases fire risk. Some passengers may disregard or not correctly follow safety rules.

- Less safety equipment.Compared to airliners, biz jets typically have fewer fire suppression tools and less protective gear on board.

Lithium battery fire smoke contains an unbreathable mix of chemicals including corrosive irritants like phosphorous oxide and hydrogen fluoride.

It seems clear that for the few rules that exist for Part 91 operations, we must be aware of them, and stick to them. And it may come as a surprise to some operators that these rules are more strict when you fly internationally – even privately.

So here’s a rundown of what you need to know.

A word about lithium-ion batteries

If you’re already familiar with a Wh rating, feel free to skip to the next section. But to understand the rules properly, it helps if you’re familiar with it first.

Watt on earth is a watt-hour (Wh)?

When we talk about how dangerous a lithium-ion battery could potentially be, we talk watt-hours. It is a measure of how much energy a battery can store and use. Think of it like the amount of fuel in a tank – it simply tells us how much power (watts) it produces over time (hours).

It also directly proportional to fire risk. If something goes wrong, all that energy can be released as heat and gas. The more in the tank, the bigger the fire.

The higher the Wh, the hotter the flames, the thicker the smoke, and critically – the harder it is to put out.

Check the battery label for its Wh rating.

Righto, onto the rules for US Part 91.

Part 91

For domestic flying in the US under Part 91, the rules for lithium-ion batteries are pretty simple.

If the batteries are being carried for personal use, Part 91 operators are (almost) entirely exempt from the US D.O.T. HAZMAT regulations that apply to commercial flights. But it’s not a free-for-all.

The PIC is still prohibited by law from carrying hazardous items onboard an aircraft in a way that might endanger people or things. This includes knowingly carrying defective batteries or packing them in a way that is dangerous or irresponsible.

Baseline safety guidelines still apply, including FAA Advisory Circulars (AC 91-78, AC 120-76D) -along with relevant Safety Alerts for Operators (SAFOs). Deviation from these can expose the operator/PIC to legal liability in the case that something bad happens.

Here’s a summary of those:

Installed batteries (in devices):

Carry these without restriction if they’re properly secured within the equipment, show no visible damage (like swelling or leakage) and are turned off.

Spare batteries:

These must be carry-on.

- Little ones (100Wh or less): There’s no limit on the number carried, but each one should be protected from short-circuits (case, sleeve, taped terminals or original packaging).

- Bigger ones (101 – 160Wh): FAA guidelines say no more than two per person. These must be individually protected using the same precautions above.

- Biggest ones (161Wh+): Not allowed without full HAZMAT compliance and operator approval. Requires UN spec packaging, shipping papers, training etc. BE CAREFUL – some higher end power banks exceed this limit.

Power banks are treated as spare batteries – this unit is equipped with a battery that exceeds 290Wh.

International operators beware!

Here’s where things get a little tricky.

Once you leave the US, some authorities no longer recognize the distinction between Part 91 (private) and other commercial flights.

Foreign authorities may enforce local rules for the batteries you carry – regardless of your Part 91 status. These are usually based upon IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations. Reportedly, this includes China, Thailand, Korea, India and the UAE.

In other words, what was acceptable in the US may not be once you’re abroad.

Foreign handlers may refuse to load spare batteries that don’t comply with IATA standards, while customs and ramp safety officers may demand battery specs and proper packaging – especially for devices like power banks, drones, camera gear and e-bikes. Devices may be confiscated if they do not comply with local guidelines.

The best solution? Just comply with IATA standards from the outset.

Where do I find these regs?

If you want to get technical – they’re defined in ICAO Doc 9284 (ICAO Technical Instructions for the Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air), and further refined under the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations.

These include packing instructions, required documents, limits of watt hour ratings, the quantity of batteries, labelling and distinctions between passenger and cargo aircraft.

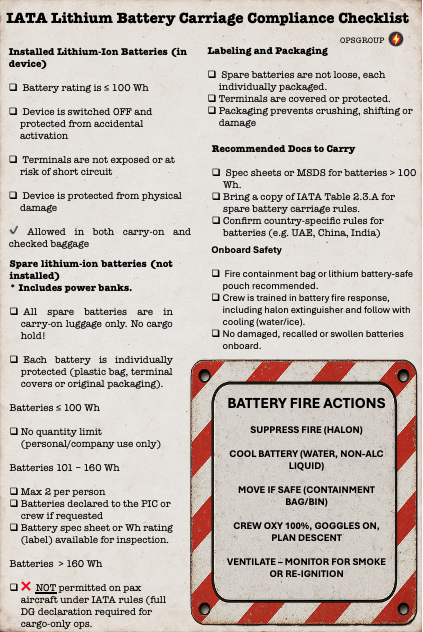

Three million pages of DG-related dread building? Worry not. We’ve put together a quick checklist of requirements/suggestions for Part 91 operators to help them stay out of trouble when carrying batteries outside of the US:

Fire containment

You might already have fire containment bags onboard, but there are other types of containment devices worth considering.

Some of the newer hard-sided designs offer features like hands-free collection, blast protection for the user, and the ability to inject water to help interrupt thermal runaway. Check out this one!

These boxes aim to reduce the risk to crew during an incident and address some limitations of soft bags, which can be difficult to use safely without two people – a challenge on smaller aircraft operating under Part 91 or 135. With recent incidents showing how violent lithium battery fires can be, having an effective containment method onboard is increasingly important.

Don’t forget to report

For Part 91 private flights, the US FAA requires operators to report any case of battery fire, smoke, overheating or thermal runaway aboard an aircraft within 72 hours. The form for this is DOT 5800.1.

ICAO may also require a report if the event qualifies as a serious incident or accident. You are not required to report directly to IATA – it’s only voluntary.