Industry heavyweight Airbus is currently running an innovative new trial over the North Atlantic that has potential to change the way we fly in oceanic airspace – and ANSPs Eurocontrol, NAT, DNSA and Navcanada are all on board. It’s called wake harnessing, and it was invented by geese. Okay maybe not ‘invented’ – but certainly provided by nature.

Geese, you say?

Geese have already left their mark on aviation history in ways that that we’d probably like to forget. So, it seems only fair that they do something positive for the industry too.

And now it seems that they are (unintentionally, but we’ll still take it). When a flock of Canada Geese infamously downed an airliner over New York back in 2009, they were flying in formation.

They were doing that because they were going somewhere and using each other to make things easier. Geese are known fly 1500 miles in a single day. That’s only possible because they use very little energy doing it.

So why do we care?

One word: biomimicry. Or in more simple terms – copying nature. When we want to figure out how to do something that we don’t know how to do, it’s often worth looking out the window. Nature, it seems, always finds a way.

Copying nature – look familiar?

Enter aviation. When it comes to fuel, it is facing a couple of big problems. The first is that ICAO have set some seriously lofty goals for improving fuel efficiency and carbon emissions. While the other issue is dosh. Jet fuel is expensive and modern aircraft use a lot of it. Reducing fuel burn is big business, especially in an environment where profit margins are tiny.

There are solutions coming. Sustainable aviation fuel and next-gen turbine engine design have been making headlines recently. But behind the scenes Airbus has been turning to nature to help solve the problem using existing technologies we have today and by changing the way we fly – and it’s all thanks to geese.

The Flying-V

Geese fly long distances in formation. Have you ever wondered why?

It’s because they are using something called wake energy retrieval. It’s a really fancy term for riding each other’s wave. It’s the result of countless years of evolution and it may have big implications for airplanes.

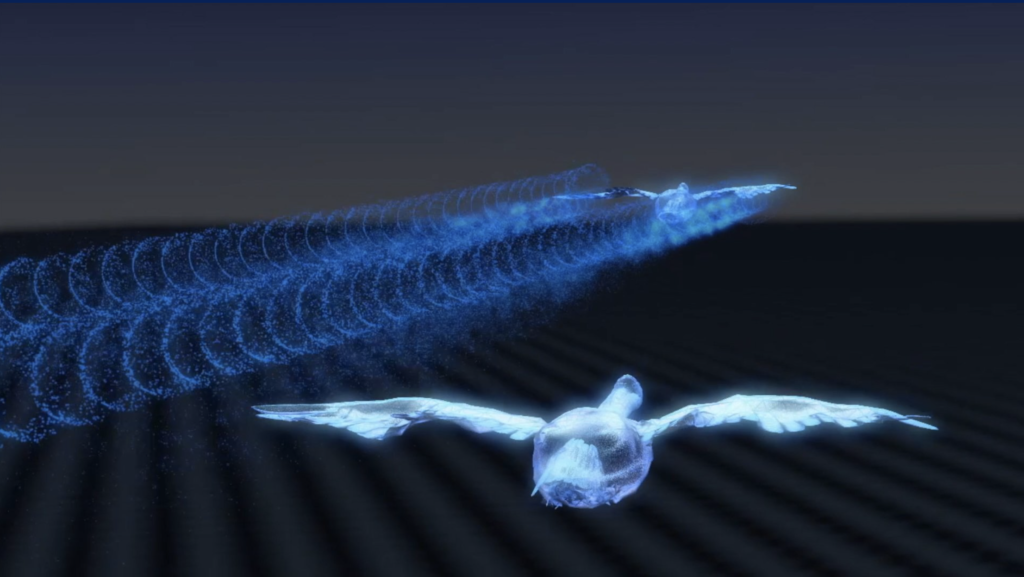

Here’s how it works: When a bird flaps its wings its tips creates vortices. In the same way that our man-made wings do. These vortices create a horizontal swirl of air – an outer upward component and an inner downward one.

The reason why birds fly in a V is because if they position themselves in such a way that their wings stay in upward-moving air from the bird in front, they can effectively fly in an updraft, constantly. Which means they flap less and travel further.

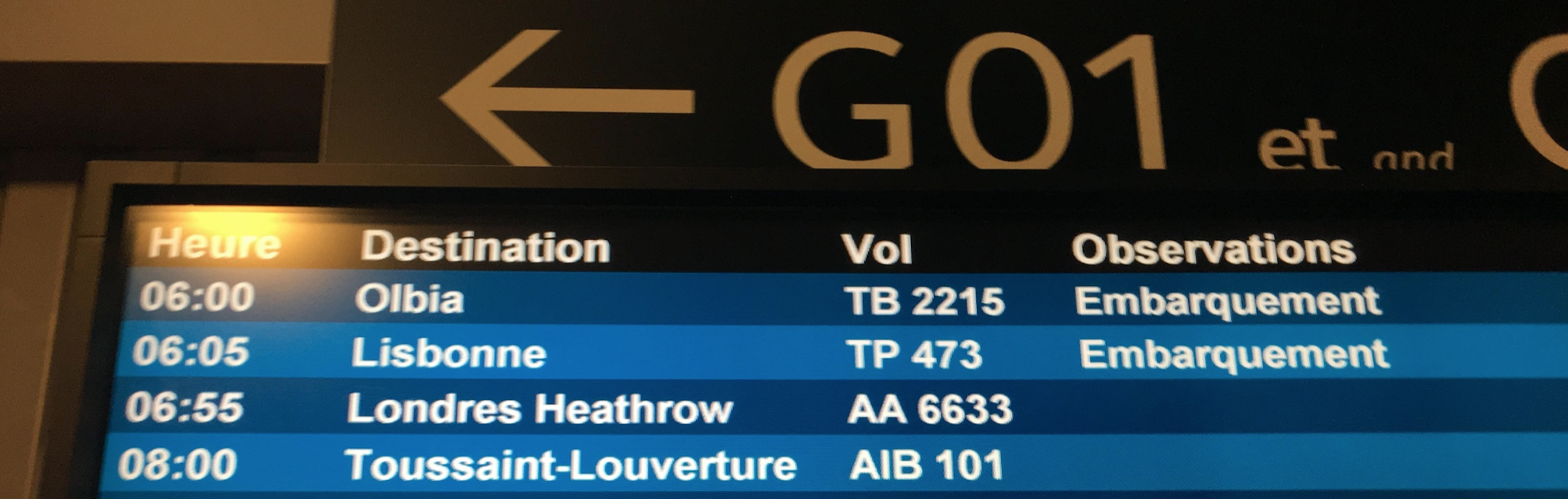

Each bird harnesses the energy lost from the wake of the bird in front. Courtesy: Airbus

What if airplanes did the same thing (but with less flapping)?

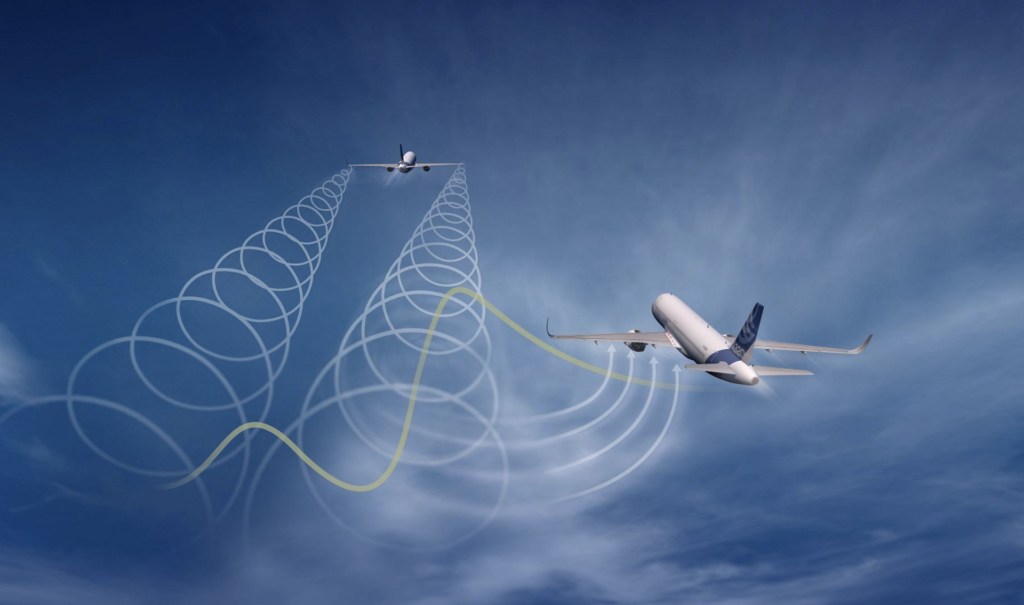

Airbus thinks that’s a good question. Since 2016 they have been copying geese by flying large jets in formation so that the trailing aircraft ‘rides the wake’ of the one in front.

It turns out that if you find just the right spot, not only is it smooth for the passengers, but also very fuel efficient. Get this – Airbus have shown fuel savings of five to ten percent simply due to the effects of this phenomenon, and potential to reduce overall climate impact by twenty-five percent.

Copying nature: Riding the smooth updraft from the aircraft in front. Courtesy: DLR Aerospace

They’re heavyweight numbers. That’s because by flying in the upward component of the wake from the aircraft in front, we are essentially getting free lift. Or in other words, ‘harnessing’ energy we’d otherwise lose – which is why the concept is also known as ‘wake harnessing’.

It’s almost as though the trailing aircraft is flying in a gentle descent while level. That means less thrust, less fuel and less emissions.

But here’s the kicker – you have to get close. Like real close. Airbus have found the optimum distance between aircraft is only 1.5nm. That’s a fraction of the spacing applied by ATC. But with existing technologies like TCAS and ADS-C it’s not unreasonable to think that this can be achieved safely.

Something we’re not used to in the sky…

Airbus have called the project Fello’fly.

And here’s how it works.

ETAs would be used by ATC at feeder waypoints to set aircraft up for their ‘wake energy retrieval pairing’- i.e. formation. The aircraft will still be separated both horizontally and vertically, but close enough for the pairing process to begin.

Responsibility for separation will then be handed to the two aircraft. Using newly developed FMS software, the trailing airplane will slowly close in on the leading one until it is positioned in the optimum spot for wake harnessing. There it will stay until the two aircraft part ways again. The lead aircraft will be responsible for talking to ATC while in formation.

But it’s not all smooth sailing.

While the idea has some serious potential there are some fairly obvious hurdles that would need to be overcome:

Wasting energy. The idea only works if aircraft don’t waste energy flying at sub-optimal speeds to make it happen. In other words, loitering or playing catch up. Which means it will be difficult to achieve for aircraft departing the same airport.

Instead the answer may lie in new software. For instance, German researchers have developed ‘MultiFly’ – a system that identifies jets that can be paired together based on type, location and how long they will be on the same route.

Different aircraft. Unlike a flock of geese, all aircraft types are different. 1.5nm may be optimal for a pair of A350s, but more testing needs to be done to find the sweet spot for all possible combinations of jets. Both aircraft would also need to have the same optimal cruise speed – otherwise all the gains would be pointless.

Then there is the raft of regulatory changes that would be required to make sure this can all happen safely.

There are some challenges to flying in formation.

Full Speed Ahead

Despite the obvious challenges that wake harnessing presents, if they can be overcome the potential benefits are obvious. Airbus is pressing ahead with the project and hope to make it reality in oceanic airspace by the middle of the decade.

Considering the growth potential of the industry in a post-Covid world, formation flight may be the next big step in cleaner and more efficient flying.

Who’d have ever thought we get there with the help of geese?